A BBC News article by Camila Ruz & Justin Parkinson.

The film Suffragette, which is due for release, portrays the struggle by British women to win the vote. They were exposed to violence and intimidation as their campaign became more militant. So they taught themselves the martial art of jiu-jitsu.

Edith Garrud was a tiny woman. Measuring 4ft 11in (150cm) in height she appeared no match for the officers of the Metropolitan Police – required to be at least 5ft 10in (178cm) tall at the time. But she had a secret weapon.

In the run-up to World War One, Garrud became a jiu-jitsu instructor to the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), better known as the suffragettes, taking part in an increasingly violent campaign for votes for women.

Sick of the lack of progress, they resorted to civil disobedience, marches and illegal activities including assault and arson.

The struggle in the years before the war became increasingly bitter. Women were arrested and, when they went on hunger strike, were force-fed using rubber tubes. While out on marches, many complained of being manhandled and knocked to the ground. Things took a darker turn after “Black Friday” on 18 November 1910.

Black Friday protest, 1910: Suffragettes were assaulted by police and men in the crowd

A group of around 300 suffragettes met a wall of policemen outside Parliament. Heavily outnumbered, the women were assaulted by both police and male vigilantes in the crowd. Many sustained serious injuries and two women died as a result. More than 100 suffragettes were arrested.

“A lot said they had been groped by the police and male bystanders,” says Elizabeth Crawford, author of The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide. “After that, women didn’t go to these demonstrations unprepared.”

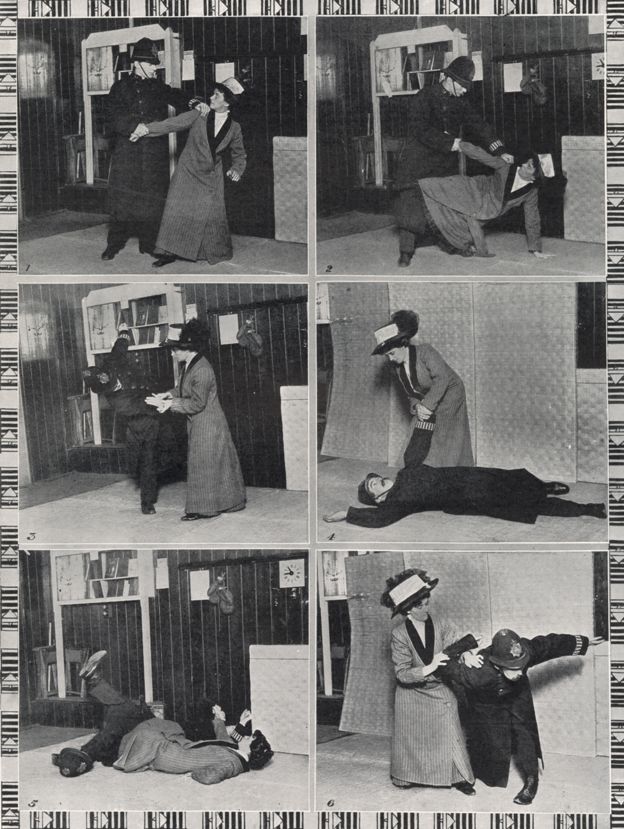

Some started putting cardboard over their ribs for protection. But Garrud was already teaching the WSPU to fight back. Her chosen method was the ancient Japanese martial art of jiu-jitsu. It emphasised using the attacker’s force against them, channelling their momentum and targeting their pressure points.

A suffragette’s guide to self-defence

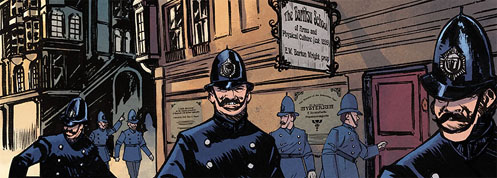

The first connection between the suffragettes and jiu-jitsu was made at a WSPU meeting. Garrud and her husband William, who ran a martial arts school in London’s Golden Square together, had been booked to attend. But William was ill, so she went alone.

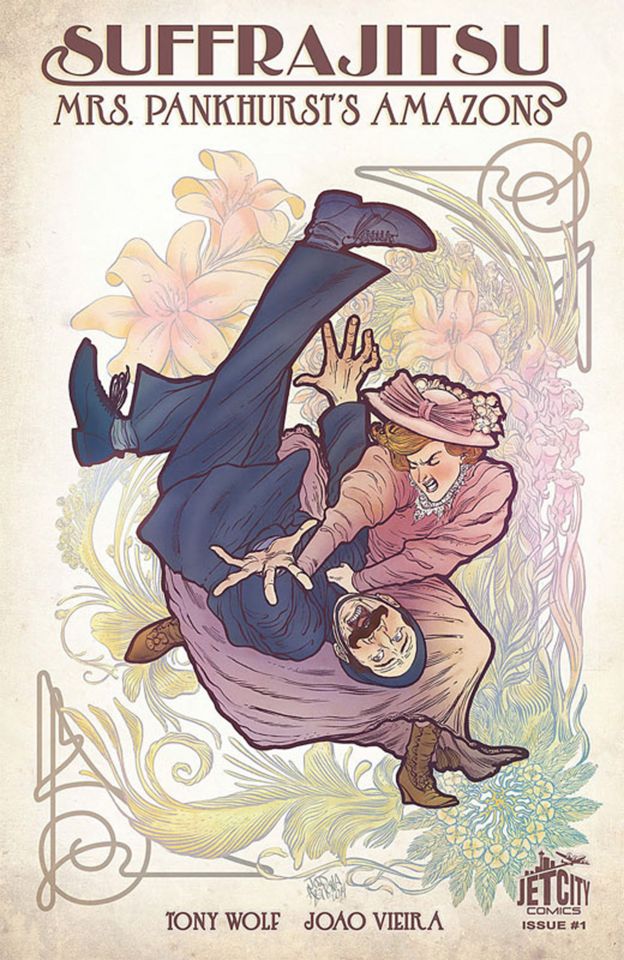

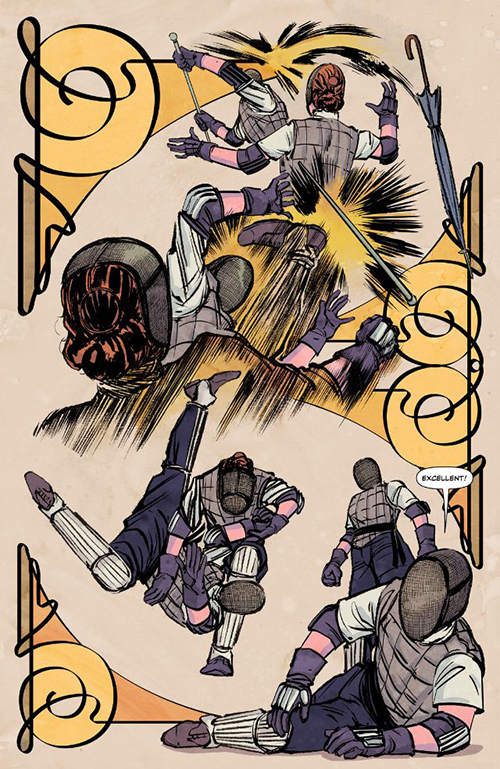

“Edith normally did the demonstrating, while William did the speaking,” says Tony Wolf, writer of Suffrajitsu, a trilogy of graphic novels about this aspect of the suffragette movement. “But the story goes that the WSPU’s leader, Emmeline Pankhurst, encouraged Edith to do the talking for once, which she did.”

Garrud began teaching some of the suffragettes. “At that time it was more about defending themselves against angry hecklers in the audience who got on stage, rather than police,” says Wolf. “There had been several attempted assaults.”

By about 1910 she was regularly running suffragette-only classes and had written for the WSPU’s newspaper, Votes for Women. Her article stressed the suitability of jiu-jitsu for the situation in which the WSPU found itself – that is, having to deal with a larger, more powerful force in the shape of the police and government.

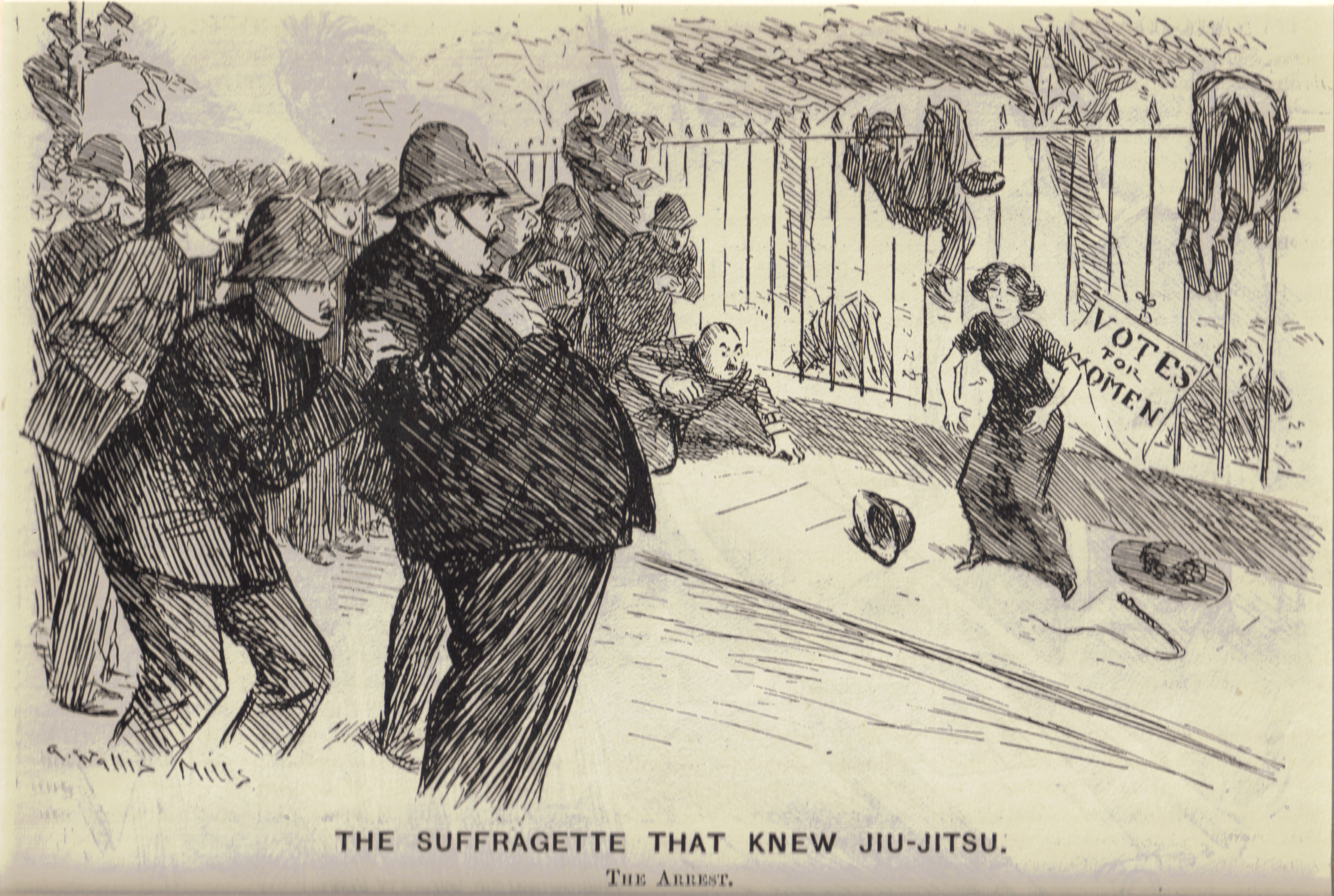

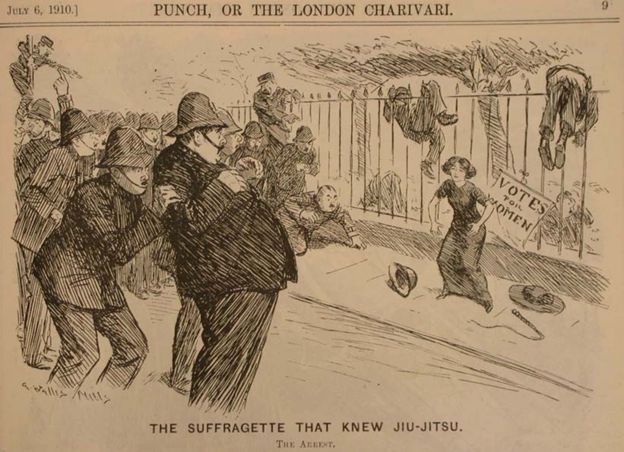

The press noticed. Health and Strength magazine printed a satirical article called “Jiu-jitsuffragettes”. Punch magazine showed a cartoon of Garrud standing alone against several policemen, entitled “The suffragette that knew jiu-jitsu”. The term “suffrajitsu” soon came into common use.

“They wouldn’t have expected in those days that women could respond physically to that kind of action, let alone put up effective resistance,” says Martin Dixon, chairman of the British Jiu-Jitsu Association. “It was an ideal way for them to handle being grabbed while in a crowd situation.”

The Pankhursts agreed and encouraged all suffragettes to learn the martial art. “The police know jiu-jitsu. I advise you to learn jiu-jitsu. Women should practice it as well as men,” said Sylvia Pankhurst, daughter of Emmeline, in a 1913 speech.

As the years went on, confrontations between police and suffragettes became more intense. The so-called Cat and Mouse Act in 1913 allowed hunger-striking prisoners to be released and then re-incarcerated as soon as they had recovered their health.

“The WSPU felt that as Mrs Pankhurst had such a vital role to play as motivator and figurehead for the organisation that she was too important to be recaptured,” says Emelyne Godfrey, author of Femininity, Crime and Self-Defence in Victorian Literature and Society.

She needed protectors so Garrud formed a group called The Bodyguard. It consisted of up to 30 women who undertook “dangerous duties,” explains Godfrey. “Sometimes all they would get would be a phone call and instructions to follow a particular car.”

The Bodyguard, nicknamed “Amazons” by the press, armed themselves with clubs hidden in their dresses.

They came in handy during a famous confrontation known as the “Battle of Glasgow” in early 1914.

The Bodyguard travelled overnight from London by train, their concealed clubs making the journey uncomfortable. A crowd was waiting to see Emmeline Pankhurst speak at St Andrew’s Hall. But police had surrounded it, hoping to catch her.

Pankhurst evaded them on her way in by buying a ticket and pretending to be a spectator. The Bodyguard then got into position, sitting on a semi-circle of chairs behind the speaker’s podium.

Suddenly Pankhurst appeared and started speaking. She did so for half a minute before police tried to storm the stage.

But they became caught on barbed wire hidden in bouquets. “So about 30 suffragettes and 50 police were involved in a brawl on stage in front of 4,000 people for several minutes,” says Wolf.

Eventually police overwhelmed The Bodyguard and Pankhurst was once again arrested. But the difficulty they had in dragging her away showed just how effective her guards had become.

Garrud did not just teach them physical skills. They had also learnt to trick their opponents. In 1914, Emmeline Pankhurst gave a speech from a balcony in Camden Square.

When she emerged from the house in a veil, escorted by members of The Bodyguard, the police swooped in. Despite a fierce fight she was knocked to the ground and dragged away unconscious. But when the police triumphantly unveiled her, they realised she was a decoy. The real Pankhurst had been smuggled out in the commotion.

The emphasis on skill to defeat and outwit a larger opponent was what first impressed Garrud about jiu-jitsu. She came across it when her husband William attended a martial arts exhibition in 1899 and started taking lessons.

Garrud was soon teaching it herself and became one of the first female martial art instructors in the West. In exhibitions, she would wear a red gown and invite a martial arts enthusiast dressed as a policeman to attack her.

“As far as the suffragettes were concerned, she was very much in the right place at the right time,” says Wolf.

“Jiu-jitsu had become something of a society trend, with women hosting jiu-jitsu parties, where they and their friends underwent instruction.”

Garrud and her jiu-jitsu students continued their fight for the vote until a bigger battle engulfed them all. At the outbreak of WW1, the suffragettes concentrated on helping the war effort.

At the end of the war, in 1918, the Representation of the People Act was finally passed. More than eight million women in the UK were given the vote. But women would not get the same voting rights as men until 1928.

As time passed, The Bodyguard and their trainer began to be forgotten. “It was the leaders that wrote the books and set the history,” explains Crawford. The stories of those who helped them were less likely to be recorded.

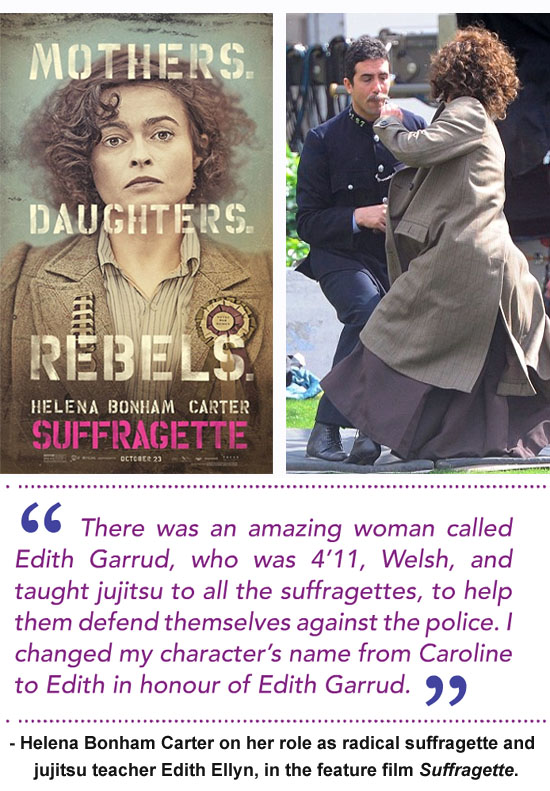

Edith Garrud does not feature in the new film but one of its stars, Helena Bonham Carter, has paid her own tribute by changing her character’s name from Caroline to Edith in her honour.

She was “an amazing woman” whose fighting method was not about brute force, Bonham Carter has said. “It was about skill.”

Helena Bonham Carter’s character in the film Suffragette is named Edith in homage to Edith Garrud

It was this skill that helped the suffragettes take on powerful opponents. As Garrud recalled in an interview in 1965, a policeman once tried to prevent her from protesting outside Parliament. “Now then, move on, you can’t start causing an obstruction here,” he said. “Excuse me, it is you who are making an obstruction,” she replied, and tossed him over her shoulder.

Suffragette is literally the first feature film to offer a dramatic representation of the radical women’s suffrage movement in England. As the movie has already been

Suffragette is literally the first feature film to offer a dramatic representation of the radical women’s suffrage movement in England. As the movie has already been  That noted, the film introduces protagonist Maud Watts (Carey Mulligan), a 24 year old East End laundress whose only joy in life is her family – husband Sonny (Ben Whishaw) and young son George (Adam Michael Dodd). Maud was born in the laundry; her mother died there when Maud was a young girl, the victim of an industrial accident, and Maud herself now bears the scars of a lifetime’s labor in that dangerous environment.

That noted, the film introduces protagonist Maud Watts (Carey Mulligan), a 24 year old East End laundress whose only joy in life is her family – husband Sonny (Ben Whishaw) and young son George (Adam Michael Dodd). Maud was born in the laundry; her mother died there when Maud was a young girl, the victim of an industrial accident, and Maud herself now bears the scars of a lifetime’s labor in that dangerous environment.

The police then violently disperse the suffragette crowd, striking women down with their truncheons and dragging them off to prison. The level of violence depicted is on the very extreme end of the scale of reported police action against suffragette protesters. The impression given is that the police assault was virtually unprovoked; this scene may have been inspired by the infamous

The police then violently disperse the suffragette crowd, striking women down with their truncheons and dragging them off to prison. The level of violence depicted is on the very extreme end of the scale of reported police action against suffragette protesters. The impression given is that the police assault was virtually unprovoked; this scene may have been inspired by the infamous

In sum, we unreservedly recommend the film to fans of the graphic novel. The cast is uniformly excellent and the evocation of London circa 1912/13 is beautifully executed. To some extent, in fact, the events of Suffragette can be viewed as an immediate prequel to those of the Suffrajitsu trilogy; it’s very easy to imagine Maud Watts as one of Mrs. Pankhurst’s Amazons.

In sum, we unreservedly recommend the film to fans of the graphic novel. The cast is uniformly excellent and the evocation of London circa 1912/13 is beautifully executed. To some extent, in fact, the events of Suffragette can be viewed as an immediate prequel to those of the Suffrajitsu trilogy; it’s very easy to imagine Maud Watts as one of Mrs. Pankhurst’s Amazons.