The Suffrajitsu media blast continues with this excellent article by KUNG FU MAGAZINE journalist Lori Ann White …

Hark back to days of yore, and schoolbook pictures of the women who fought for the vote in the days leading up to the First World War. Ladies in long skirts with grim faces, marching through the city streets and wielding their weapons of choice: banners and pamphlets, signs and shouting. Motherly and grandmotherly types, in starched white shirts with lace at their throats, giving speeches and picketing City Hall. Maybe—if they were extra hard-core—being arrested and going on hunger strikes.

These women are all familiar images from both sides of the Atlantic. British and American suffragettes, who won a voice for their sisters and daughters almost 100 years ago. Noble. Uplifting.

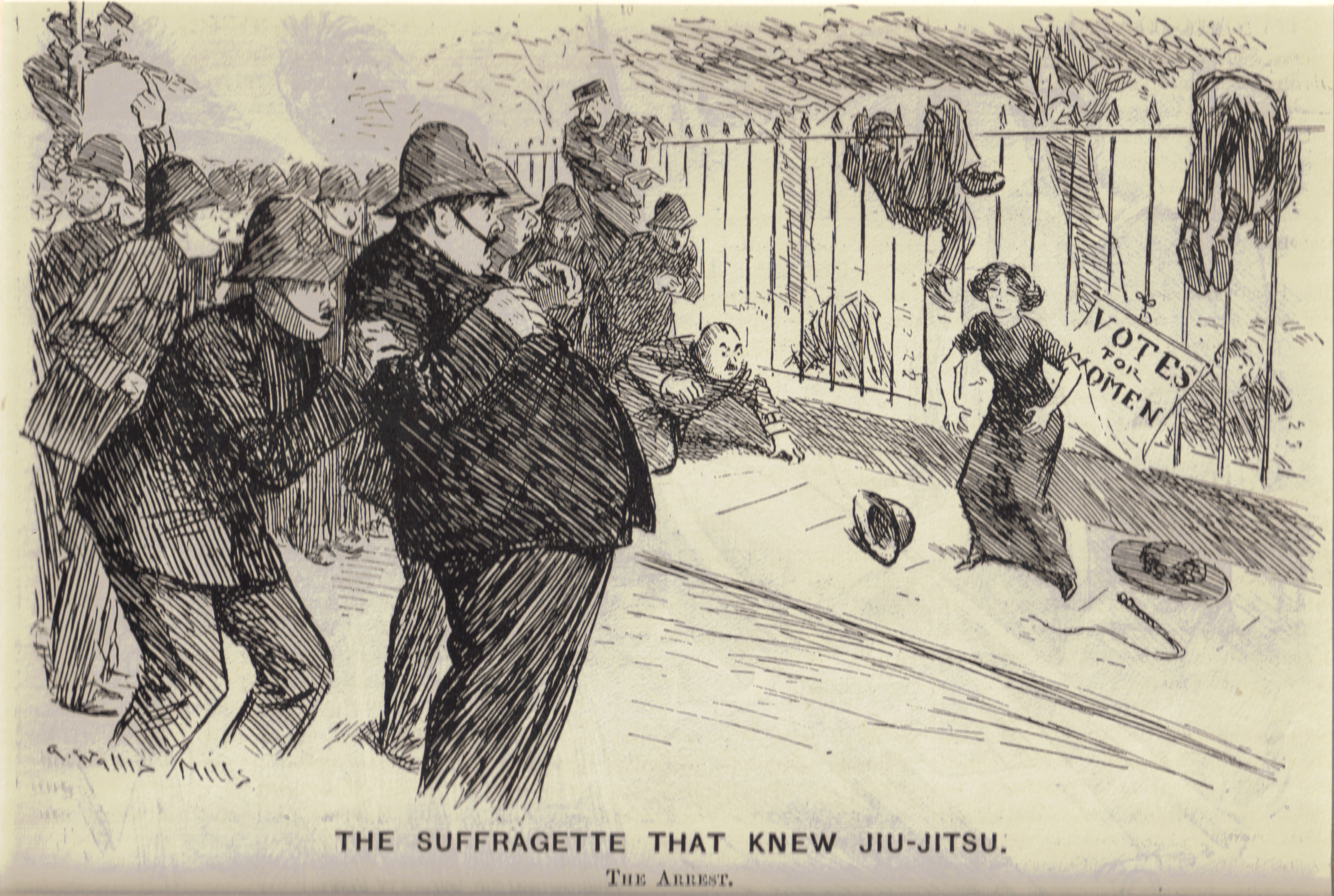

But there’s a picture that’s missing from many accounts of the history of the suffrage movement in England. A picture of the women who were totally bad-ass, with training in grappling and throws and, tucked in their bustles, clubs they were not afraid to use on the men who were trying to shut them down.

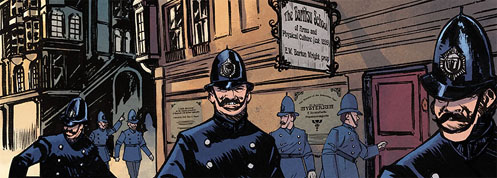

The film SUFFRAGETTE (2015) is a study of why these women wanted the skills to defend themselves. It shows the brutality of the London bobbies, who waded into demonstrations and meetings with their own fists and truncheons. More than that, it shows the assaults and insults women had to deal with every day of their lives, from their bosses, their husbands, random men on the street.

One very short scene in the film shows the heroine, Maud Watts (Carey Mulligan, an Edwardian Everywoman) getting expertly dumped to the mat by Edith Ellyn (Helena Bonham Carter, a steely, seasoned soldier of the cause). This is a welcome hint, but only a hint of the martial training of London suffragettes.

The reality is fascinating: A group of dedicated women trained in a hybrid art called Bartitsu who served as bodyguards for wanted suffragettes, security detail for events, and de facto Secret Service detail for Emmeline Pankhurst (Meryl Streep in the film), the leader of the Women’s Social and Political Union, representing the more radical faction of the suffrage movement.

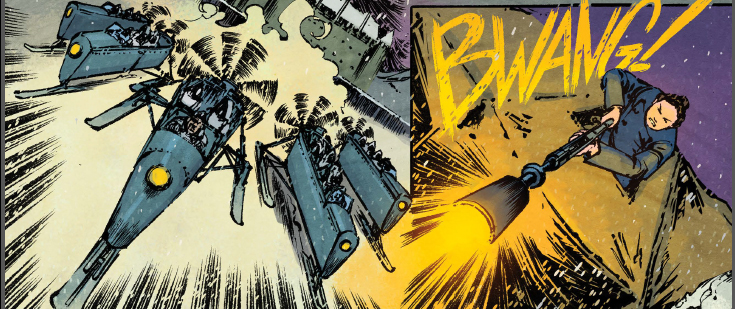

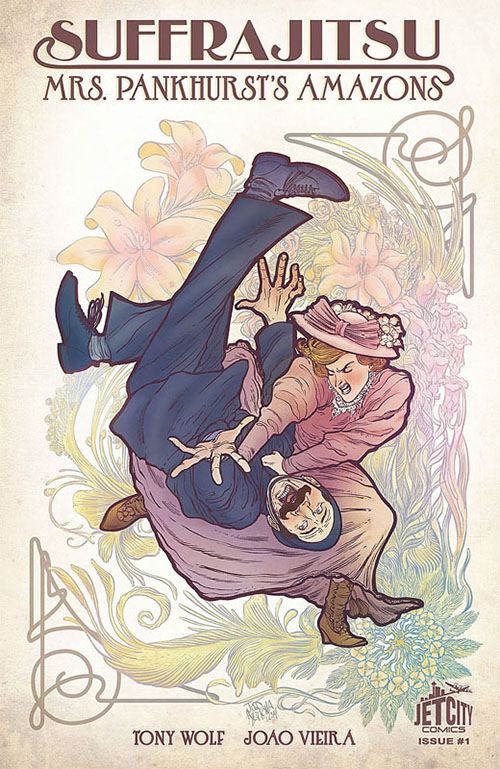

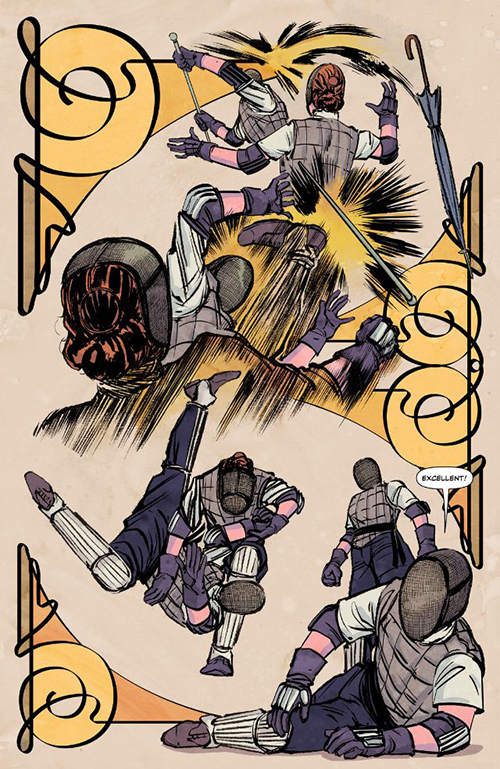

Another option for learning more about these “jiujitsuffragettes,” as dubbed by the press of the day (and having fun doing it), is the graphic novel trilogy, “SUFFRAJITSU: MRS. PANKHURST’S AMAZONS” (2015), written by Tony Wolf, with art by Joao Vieira.

Set in early 1914, at the height of the suffragette movement in London, SUFFRAJITSU introduces us to the Bartitsu-trained women who protect Emmeline Pankhurst, and two of their real-life instructors, Edith Garrud, the women’s jiujitsu instructor at the Bartitsu Club, and the mysterious Miss Sanderson, who was actually Marguerite Vigny, the wife of Pierre Vigny, the cane and savate instructor at the Bartitsu Club.

“The first part of the story is very closely based on real history,” says author Wolf, “as the Amazons engage in escalating confrontations with the police. The strategies of jiujitsu were seen as a metaphor for the womens’ fight to get the vote, and the Amazons served as symbols of women’s defiance against the state’s authority as well as functional bodyguards. Both sides were really engaged in an all-out, hearts-and-minds propaganda battle by that point.”

Wolf is a martial artist, martial arts scholar, fight choreographer and stuntman whose credits include developing the different styles used by the various races in Peter Jackson’s LORD OF THE RINGS trilogy (2001, 2002, 2003). He got his start in eastern styles such as Taekwondo, but became intrigued by the history of martial arts in Europe. His researches led him to Bartitsu, a hybrid style developed by E. W. Barton-Wright (hence the name), a British engineer who spent three years in Japan, which he introduced in London in 1898, according to Wolf.

“Bartitsu was an eccentric ‘mixed martial art‘ combining boxing, jiujitsu, kicking and the Vigny method of self-defense with a walking stick,” says Wolf. It is quite probably the source of Sherlock Holmes’ “Baritsu” style.

In about 2002 Wolf used what he calls “historical detective work and practical pressure-testing” to bring back the lost art of Bartitsu. “Reviving Bartitsu as a sort of gentlemanly Jeet Kune Do, or maybe ‘Edwardian Dog Brothers,’ has been my main martial arts interest since then,” he says.

Wolf’s first exposure to Mrs. Pankhurst’s Amazons happened much earlier, though.

“I remember first coming across an anecdote about the ‘jiujitsuffragettes’ in a martial arts history book when I was a teenager,” he says. “Apparently, young, middle-class London suffragettes would shinny down the drainpipes and sneak off to secret self-defense classes in the dead of night.”

An appealing image to a rebellious teen, but Wolf did not begin to study them in earnest until he was researching the history of Bartitsu. “I came across more and more information about the suffragette Amazons. Eventually I incorporated that information into some Bartitsu-themed books and a documentary I co-produced in 2010.”

Then well-known science fiction and fantasy author Neal Stephenson, a Bartitsu aficionado, approached Wolf to write the story of the Edwardian Amazons for Stephenson’s vast shared-world project, the Foreworld Saga.

“I think [Stephenson] was really taken by the idea of a group of bad-ass Edwardian ladies and wanted to see that happen somewhere in the Foreworld,” Wolf says.

With more experience in non-fiction than fiction, Wolf approached the project with some hesitation. “It was a bit of a leap of faith for Neal to get me involved in the Foreworld project,” Wolf says. “I’m very grateful that he did, though, because it was a blast to get to work creatively with all the jiujitsuffragette material I’d been gathering for years.”

The truth is almost as strange, though, and provides a fascinating glimpse into women in the martial arts in the early 20th century. A number of circumstances—some positive, some less so—had begun to open up the pursuit of martial arts to women.

“Women who wanted to learn jiujitsu weren’t typically considered to be less than ladylike,” Wolf says. “It dovetailed nicely with several other popular trends, including ‘physical culture’ or exercise training, which was generally looked on with good favor, and there was also a lot of popular enthusiasm for Japanese culture at the time.”

On a darker note, says Wolf, “There was a growing awareness of assaults in public spaces, on board trains, and so on, especially as more and more women went into employment and started to travel in cities without chaperones.”

It’s probable that both Marguerite Vigny and Edith Garrud developed new techniques for the women under their tutelage, says Wolf. “Madame Vigny’s system was a pragmatic adaptation of her husband’s method, based on using the umbrella or parasol as a combination of rapier and short spear,” he says, while the women learned some interesting and very effective techniques with Indian clubs, either from Garrud or through trial and error.

“There are very few specific records of how the clubs were used, but the Amazons did learn to target police constables’ helmets, because if the constables lost their helmets, they had to pay for them to be replaced,” Wolf says. Knocking a helmet off a bobby’s head generally sent him scrambling after.

The women also found a useful technique for dealing with the mounted police. “One of the suffragettes figured out that, if you struck a police horse on the back of its knee with an Indian club, the horse would sit down quickly and dump a mounted constable off its back. The horse wouldn’t be hurt, so that was a great counter-move.”

According to Wolf, the suffrage movement in the US did not employ similar tactics. “The US suffrage movement was nowhere near as radical as the suffragettes in the UK,” he says. By some accounts, the violence employed by the more radical suffragettes in London set their cause back by a few years. But following World War I the men of England realized that the women of England deserved a voice and a vote.

After all, there’s only so much you can say with your fists.