I had lately returned to my London flat following a strenuous and morally stimulating adventure in Tuscany. Sifting through the inevitable accumulation of mail, I discovered a telegram dated just the previous day. It read:

DARLING JUDITH STOP FAR TOO LONG STOP URGENT THAT WE MEET AT EARLIEST CONVENIENCE STOP PERSI

followed by a telephone number.

“Persi” could only be my old school chum, Persephone Wright. The particulars were quickly arranged and so I set out for the Café Royal in Regent Street that very afternoon, most curious as to what might have become of Persi in the decade since we had last met.

She had never been precisely demure, but Persephone’s appearance and manner as she swept into the gilt-and-turquoise café was positively Bohemian, all gypsy shawls, art nouveau jewellery, dark honey hair and feline grace.

“Judith, dear”, she began as soon as we broke our embrace, “it’s smashing to see you! Now, I do hope you’ll be able to help – my friend Armand has just been arrested and things are in an awful state!”

This occasioned some raised eyebrows amongst the other café patrons and I ushered her into a booth post-haste.

“Well, I shall do what I can to help,” I began once we were settled, “but please understand that I am not so much a detective as simply an inquisitive woman with a few unusual talents.”

Chief amongst those talents, as my regular readers will be aware, is my ability to read lips, a skill I have honed since young childhood and which I currently employ in my occupation as a teacher of the deaf. It has occasionally happened that I am able to “overhear” by sight certain confidences of an illicit nature, which I have felt morally compelled to investigate; by these means have a number of frauds, thieves and even murderers been brought to justice.

Over our afternoon repast of milky mint tea and crumpets, Persephone informed me that her uncle Edward was the proprietor of the famous Bartitsu Club in Shaftesbury Avenue, where the cream of London society took their exercise and learned the noble arts of self defence. The unfortunate “Armand” was Armand Cherpillod, the Club’s professor of physical culture and wrestling. Persephone described him as a kind and stalwart but unworldly man, of humble rural stock, who had emigrated from Switzerland some years earlier, at her uncle’s invitation. Since then, she said, Armand had often, and rather successfully, represented the Bartitsu Club in wrestling challenges upon the Tivoli and Alhambra stages.

“And what has brought this great wrestler so low?” I inquired.

Persi lit an exotic cigarette, perhaps to soothe her nerves.

“He has been accused of theft,” she said somberly. “The police found stolen property in his flat – a precious diamond ring that apparently belongs to Lady Lucy Duff-Gordon, the wife of Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon, who was himself a student of Armand’s.”

“Lady Duff-Gordon – better known as Lucile? The fashion designer?” I asked.

“The very same.”

“But you believe that Armand is innocent?”

“Absolutely so. Armand says that he was, in fact, given this ring as a gift by another of his wrestling students, a woman named Marjorie. I strongly suspect that she is the true thief, or at least the villain’s accomplice.” Persephone’s deep blue eyes narrowed as she drew pensively on her cigarette.

“We’ve seen nothing of Marjorie since Armand was arrested, and she’d never missed a class before. Of course, Uncle Edward is very concerned, not just for Armand’s well-being but also for the honour of the Bartitsu Club. A scandal might ruin him.”

“Well then,” I said, “we must find this woman as soon as we can. I assume that you have explained all of this to the police?”

At this, Persi frowned again.

“Of course, but I’m afraid there’s little that I, or any associate of the Bartitsu Club, can say to the police that would influence them for the better,” she said. “They are thoroughly suspicious of the lot of us, at the present time.”

“But why?”

Persi exhaled a thin stream of smoke and then, knowing my talent at lip reading, spoke silently, her lips and tongue forming the words:

“Judith, I understand that you support the fight for women’s suffrage?”

I nodded in assent.

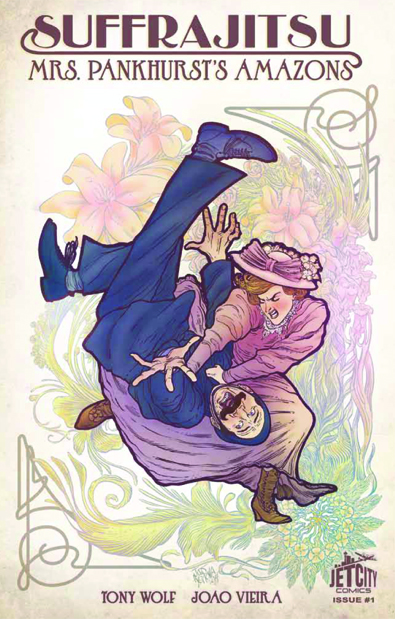

“You should know that the Club is the headquarters of Mrs. Pankhurst’s Amazon guards. The police are aware of that, though they’ve never been able to prove it; thus our dilemma.”

I understood at once. The Amazons were the subject of much newspaper speculation and street gossip; aside from serving as Mrs. Pankhurst’s personal bodyguards in sometimes violent affrays with the constabulary, they were rumoured to engage in no small amount of criminal activity to draw attention to their cause. I knew, however, that they took great pains to ensure that their protests by vandalism and arson caused no-one any physical harm. While I would not normally associate myself with lawbreakers, as far as I was concerned, the Amazons were serving the higher moral good.

“All right, then,” I said, “let’s pay a visit to your uncle’s Club.”

It was about a quarter to six o’clock when Persephone escorted me to the Bartitsu School of Arms in Soho, the two of us walking arm-in-arm and reminiscing about our girlhood escapades. We turned the slight left from Regent Street into Shaftesbury Avenue and five minutes later arrived at the Club, number 67. An ornate sign announcing the business name and that of its proprietor hung above the door.

Upon entering the spacious, high-ceilinged exercise hall of the Bartitsu Club, my predominant impression was of a curiously formal street brawl in progress. Most of the participants were women, and I wondered whether these were the mysterious Amazons themselves in training. Spread throughout the hall were about fifteen combatants, wearing dark blue exercise blouses and bloomer pants over their stockings, all swinging and jabbing, grappling and falling. One woman was shinnying her way up a thick rope that hung from the rafters, while others struck viciously at heavy leather punching bags. A group of four, attired in sabre fencing pads and helmets, appeared to be fencing with parasols!

The air was rent with occasional sharp cries (of focussed aggression, it seemed, rather than of fear or pain), the staccato smacks of fists and feet against the punching bags and the fearsome “thwap!” of bodies hurled to the mats. Altogether, it was quite a scene.

“This is Bartitsu,” Persephone confided. “My uncle’s invention and his pride and joy. It melds the best of European and Oriental antagonistics – boxing, wrestling, Monsieur Vigny’s art of self-defence with a walking stick or parasol, and Japanese jiujitsu.”

As a longtime physical culture enthusiast I had read of jiujitsu, whose principle was to employ an enemy’s weight and strength against himself, but this was my first experience of it in person. Persi pointed out the two young professors of the art, Tani-san and Uyenishi-san, and I was instantly reminded of the shway jao wrestlers who had served as my grandparents’ bodyguards in Hong Kong. They were coaching several of the women in some impossibly acrobatic wrestling trick. I had but little time to take it in, however, for now Persephone was waving over a muscular fellow in grey leotards who, from his age (early fifties), demeanor (stern, moustachioed, vigorous) and eyes (blue, piercing) I judged correctly to be her uncle Edward.

“Thank you for coming, Miss Lee,” he said. “I do hope that you’ll be able to get to the bottom of this sorry business. Shall we retire to my office?” His accent possessed the eclectic intrigue of those who have travelled far, wide and long; it was impossible to say whether Scottish, Hindi, London English, French, German or even Japanese held sway. In any case, Mr. Barton-Wright’s voice was deep and commanding.

I accompanied the two of them as they skirted the balletic violence of the hardwood exercise floor. En route, I was surprised to recognise several of the women trainees; there was Toupie Lowther, the champion fencer and lawn tennis player, and Esme Beringer, the famous West End actress. No-one could have failed to spot the giant known popularly as Sandwina, whose fame as a circus strongwoman and wrestler was widespread.

As we entered the spartan office, I decided to take time by the forelock.

“If I may ask, Mr. Barton-Wright, who would most stand to benefit from ruining Mr. Cherpillod’s good name and the reputation of your Club? Do you have any enemies?”

Mr. Barton-Wright did not quite scowl, but his magnificent moustache twitched meaningfully. “Enemies? Oh, I should say so. Certain members of London’s wrestling fraternity come to mind; men who have been bested by Cherpillod, Tani and Uyenishi in honest matches, but who do not care to lose under any circumstances.”

He strode to the bookshelf behind his desk and withdrew a large, leather-bound scrapbook, which he laid upon the desk and flipped open. Inside were pasted pages of newspaper reports detailing the victories of his champions at the Tivoli, the Alhambra, St. James’s Hall and many other famous venues.

“Take your pick, Miss Lee,” he rumbled. “At one time or another I’ve had hard words with Jack Carkeek, Joe Carroll, the Gruhn brothers, Tom Cannon, Klemsky the Russian … the list goes on and on. Some of it’s swank, but some’s on the level.”

“Swank?” I asked.

“Music hall showmanship,” Persephone explained. “Staged arguments and bits of business to keep the punters amused and coming back day after day.”

“I see. But of the real disputants, who would you be most inclined to suspect?”

“If I had to put money on it, Miss Lee, I think Klemsky here is the likeliest malefactor,” replied Mr. Barton-Wright, showing me a publicity photograph of a beefy, balding fellow with a long, narrow moustache, crouching in a wrestling pose.

“He is not really a Russian – that’s an example of swanking, you see. His real name is John Chance. In any case, he lost fairly to Uyenishi-san, though he later claimed that he’d been hypnotised – if you can believe that! – and then to Cherpillod at catch-as-catch-can. He was very sore about that match. I’ve not seen him since then, but we’ve had some vehement exchanges via public correspondence in Health and Strength magazine. I believe that he bears us a real grudge – against Armand, especially.”

Mr. Barton-Wright closed the scrapbook with a soft thump.

“Chance has recently opened his own physical culture school in West London, called the Hammersmith Athletic Club,” Persephone offered. “He has a, well, a checkered past.”

“And perhaps,” I mused, “he believes he had reason to cause this Marjorie woman to pass the stolen diamond ring on to Mr. Cherpillod, disguised as a gift from an admiring pupil.”

“That is precisely Armand’s account of things, though I’ll be dashed if I know how to prove it,” replied Mr. Barton-Wright. “Unfortunately, none of us here ever saw the ring and he did not mention the gift until after he was arrested.”

“Whyever not?” I exclaimed. “It seems an extravagant present from a wrestling student to her professor, surely worthy of some comment.”

“Armand is a genius at wrestling, but he is also the son of a poor Swiss farmer,” said Persephone. “He’s always been ill-at-ease with ‘airs and graces’ and was probably too embarrassed to speak of the gift, precisely for the fear that it would seem extravagant or as if he were big-noting.”

She absently took out her cigarette case, noted her uncle’s reproving glance and primly put it away again.

“Armand’s humility is one of his most endearing qualities, though it’s done him no favours in this case,” she finished.

Mr. Barton-Wright nodded, a grim set to his strong jaw. “So now the poor lad languishes in Wandsworth Prison awaiting trial,” he said, “and our Club’s reputation suffers by the day. If he’s found guilty of theft …”

“Well then, I shall do what I can to investigate,” I interjected, “but while my own reputation may be one of forthrightness, I’ll confess that I’m a little worried about bearding this particular lion in his den alone.”

I turned to Persephone. “Your Amazons, Persi; might they be up for a little freelance excursion?”

She simply smiled.

Continue to Part 2 …