Here are two radio interviews with Tony Wolf, covering both the real history of the suffragette Amazons and the creation of the Suffrajitsu graphic novels:

BBC World Service:

Newstalk Ireland:

A BBC News article by Camila Ruz & Justin Parkinson.

The film Suffragette, which is due for release, portrays the struggle by British women to win the vote. They were exposed to violence and intimidation as their campaign became more militant. So they taught themselves the martial art of jiu-jitsu.

Edith Garrud was a tiny woman. Measuring 4ft 11in (150cm) in height she appeared no match for the officers of the Metropolitan Police – required to be at least 5ft 10in (178cm) tall at the time. But she had a secret weapon.

In the run-up to World War One, Garrud became a jiu-jitsu instructor to the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), better known as the suffragettes, taking part in an increasingly violent campaign for votes for women.

Sick of the lack of progress, they resorted to civil disobedience, marches and illegal activities including assault and arson.

The struggle in the years before the war became increasingly bitter. Women were arrested and, when they went on hunger strike, were force-fed using rubber tubes. While out on marches, many complained of being manhandled and knocked to the ground. Things took a darker turn after “Black Friday” on 18 November 1910.

Black Friday protest, 1910: Suffragettes were assaulted by police and men in the crowd

A group of around 300 suffragettes met a wall of policemen outside Parliament. Heavily outnumbered, the women were assaulted by both police and male vigilantes in the crowd. Many sustained serious injuries and two women died as a result. More than 100 suffragettes were arrested.

“A lot said they had been groped by the police and male bystanders,” says Elizabeth Crawford, author of The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide. “After that, women didn’t go to these demonstrations unprepared.”

Some started putting cardboard over their ribs for protection. But Garrud was already teaching the WSPU to fight back. Her chosen method was the ancient Japanese martial art of jiu-jitsu. It emphasised using the attacker’s force against them, channelling their momentum and targeting their pressure points.

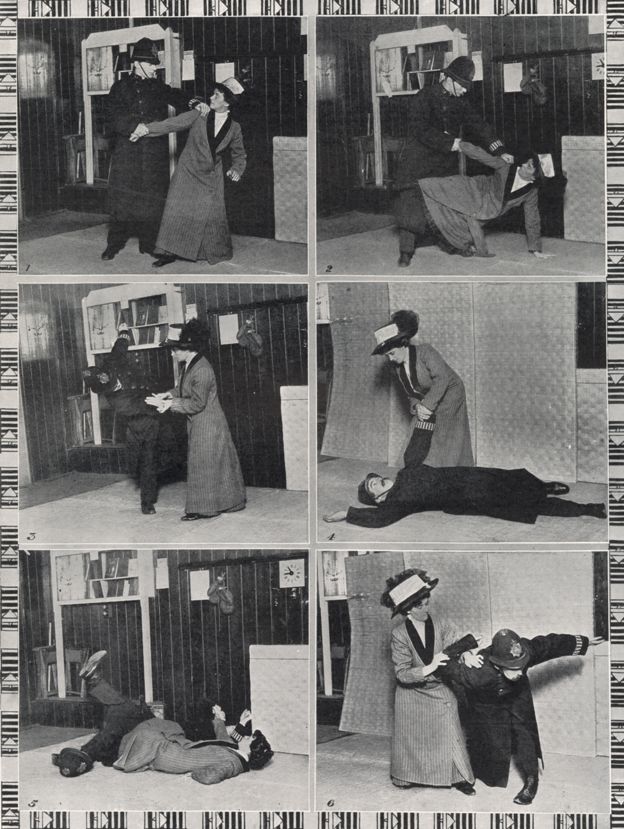

A suffragette’s guide to self-defence

The first connection between the suffragettes and jiu-jitsu was made at a WSPU meeting. Garrud and her husband William, who ran a martial arts school in London’s Golden Square together, had been booked to attend. But William was ill, so she went alone.

“Edith normally did the demonstrating, while William did the speaking,” says Tony Wolf, writer of Suffrajitsu, a trilogy of graphic novels about this aspect of the suffragette movement. “But the story goes that the WSPU’s leader, Emmeline Pankhurst, encouraged Edith to do the talking for once, which she did.”

Garrud began teaching some of the suffragettes. “At that time it was more about defending themselves against angry hecklers in the audience who got on stage, rather than police,” says Wolf. “There had been several attempted assaults.”

By about 1910 she was regularly running suffragette-only classes and had written for the WSPU’s newspaper, Votes for Women. Her article stressed the suitability of jiu-jitsu for the situation in which the WSPU found itself – that is, having to deal with a larger, more powerful force in the shape of the police and government.

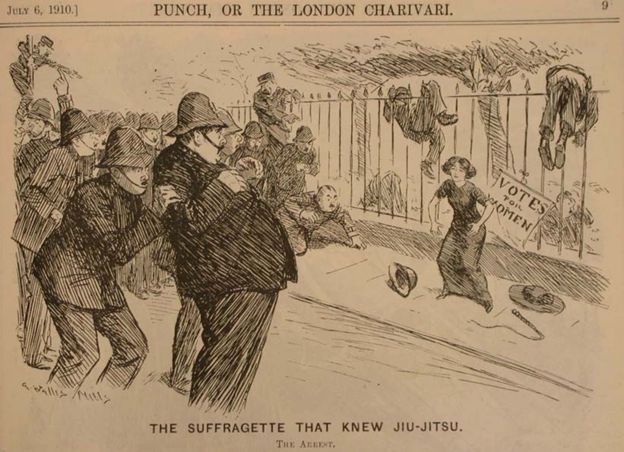

The press noticed. Health and Strength magazine printed a satirical article called “Jiu-jitsuffragettes”. Punch magazine showed a cartoon of Garrud standing alone against several policemen, entitled “The suffragette that knew jiu-jitsu”. The term “suffrajitsu” soon came into common use.

“They wouldn’t have expected in those days that women could respond physically to that kind of action, let alone put up effective resistance,” says Martin Dixon, chairman of the British Jiu-Jitsu Association. “It was an ideal way for them to handle being grabbed while in a crowd situation.”

The Pankhursts agreed and encouraged all suffragettes to learn the martial art. “The police know jiu-jitsu. I advise you to learn jiu-jitsu. Women should practice it as well as men,” said Sylvia Pankhurst, daughter of Emmeline, in a 1913 speech.

As the years went on, confrontations between police and suffragettes became more intense. The so-called Cat and Mouse Act in 1913 allowed hunger-striking prisoners to be released and then re-incarcerated as soon as they had recovered their health.

“The WSPU felt that as Mrs Pankhurst had such a vital role to play as motivator and figurehead for the organisation that she was too important to be recaptured,” says Emelyne Godfrey, author of Femininity, Crime and Self-Defence in Victorian Literature and Society.

She needed protectors so Garrud formed a group called The Bodyguard. It consisted of up to 30 women who undertook “dangerous duties,” explains Godfrey. “Sometimes all they would get would be a phone call and instructions to follow a particular car.”

The Bodyguard, nicknamed “Amazons” by the press, armed themselves with clubs hidden in their dresses.

They came in handy during a famous confrontation known as the “Battle of Glasgow” in early 1914.

The Bodyguard travelled overnight from London by train, their concealed clubs making the journey uncomfortable. A crowd was waiting to see Emmeline Pankhurst speak at St Andrew’s Hall. But police had surrounded it, hoping to catch her.

Pankhurst evaded them on her way in by buying a ticket and pretending to be a spectator. The Bodyguard then got into position, sitting on a semi-circle of chairs behind the speaker’s podium.

Suddenly Pankhurst appeared and started speaking. She did so for half a minute before police tried to storm the stage.

But they became caught on barbed wire hidden in bouquets. “So about 30 suffragettes and 50 police were involved in a brawl on stage in front of 4,000 people for several minutes,” says Wolf.

Eventually police overwhelmed The Bodyguard and Pankhurst was once again arrested. But the difficulty they had in dragging her away showed just how effective her guards had become.

Garrud did not just teach them physical skills. They had also learnt to trick their opponents. In 1914, Emmeline Pankhurst gave a speech from a balcony in Camden Square.

When she emerged from the house in a veil, escorted by members of The Bodyguard, the police swooped in. Despite a fierce fight she was knocked to the ground and dragged away unconscious. But when the police triumphantly unveiled her, they realised she was a decoy. The real Pankhurst had been smuggled out in the commotion.

The emphasis on skill to defeat and outwit a larger opponent was what first impressed Garrud about jiu-jitsu. She came across it when her husband William attended a martial arts exhibition in 1899 and started taking lessons.

Garrud was soon teaching it herself and became one of the first female martial art instructors in the West. In exhibitions, she would wear a red gown and invite a martial arts enthusiast dressed as a policeman to attack her.

“As far as the suffragettes were concerned, she was very much in the right place at the right time,” says Wolf.

“Jiu-jitsu had become something of a society trend, with women hosting jiu-jitsu parties, where they and their friends underwent instruction.”

Garrud and her jiu-jitsu students continued their fight for the vote until a bigger battle engulfed them all. At the outbreak of WW1, the suffragettes concentrated on helping the war effort.

At the end of the war, in 1918, the Representation of the People Act was finally passed. More than eight million women in the UK were given the vote. But women would not get the same voting rights as men until 1928.

As time passed, The Bodyguard and their trainer began to be forgotten. “It was the leaders that wrote the books and set the history,” explains Crawford. The stories of those who helped them were less likely to be recorded.

Edith Garrud does not feature in the new film but one of its stars, Helena Bonham Carter, has paid her own tribute by changing her character’s name from Caroline to Edith in her honour.

She was “an amazing woman” whose fighting method was not about brute force, Bonham Carter has said. “It was about skill.”

Helena Bonham Carter’s character in the film Suffragette is named Edith in homage to Edith Garrud

It was this skill that helped the suffragettes take on powerful opponents. As Garrud recalled in an interview in 1965, a policeman once tried to prevent her from protesting outside Parliament. “Now then, move on, you can’t start causing an obstruction here,” he said. “Excuse me, it is you who are making an obstruction,” she replied, and tossed him over her shoulder.

The Suffrajitsu media blast continues with this excellent article by KUNG FU MAGAZINE journalist Lori Ann White …

Hark back to days of yore, and schoolbook pictures of the women who fought for the vote in the days leading up to the First World War. Ladies in long skirts with grim faces, marching through the city streets and wielding their weapons of choice: banners and pamphlets, signs and shouting. Motherly and grandmotherly types, in starched white shirts with lace at their throats, giving speeches and picketing City Hall. Maybe—if they were extra hard-core—being arrested and going on hunger strikes.

These women are all familiar images from both sides of the Atlantic. British and American suffragettes, who won a voice for their sisters and daughters almost 100 years ago. Noble. Uplifting.

But there’s a picture that’s missing from many accounts of the history of the suffrage movement in England. A picture of the women who were totally bad-ass, with training in grappling and throws and, tucked in their bustles, clubs they were not afraid to use on the men who were trying to shut them down.

The film SUFFRAGETTE (2015) is a study of why these women wanted the skills to defend themselves. It shows the brutality of the London bobbies, who waded into demonstrations and meetings with their own fists and truncheons. More than that, it shows the assaults and insults women had to deal with every day of their lives, from their bosses, their husbands, random men on the street.

One very short scene in the film shows the heroine, Maud Watts (Carey Mulligan, an Edwardian Everywoman) getting expertly dumped to the mat by Edith Ellyn (Helena Bonham Carter, a steely, seasoned soldier of the cause). This is a welcome hint, but only a hint of the martial training of London suffragettes.

The reality is fascinating: A group of dedicated women trained in a hybrid art called Bartitsu who served as bodyguards for wanted suffragettes, security detail for events, and de facto Secret Service detail for Emmeline Pankhurst (Meryl Streep in the film), the leader of the Women’s Social and Political Union, representing the more radical faction of the suffrage movement.

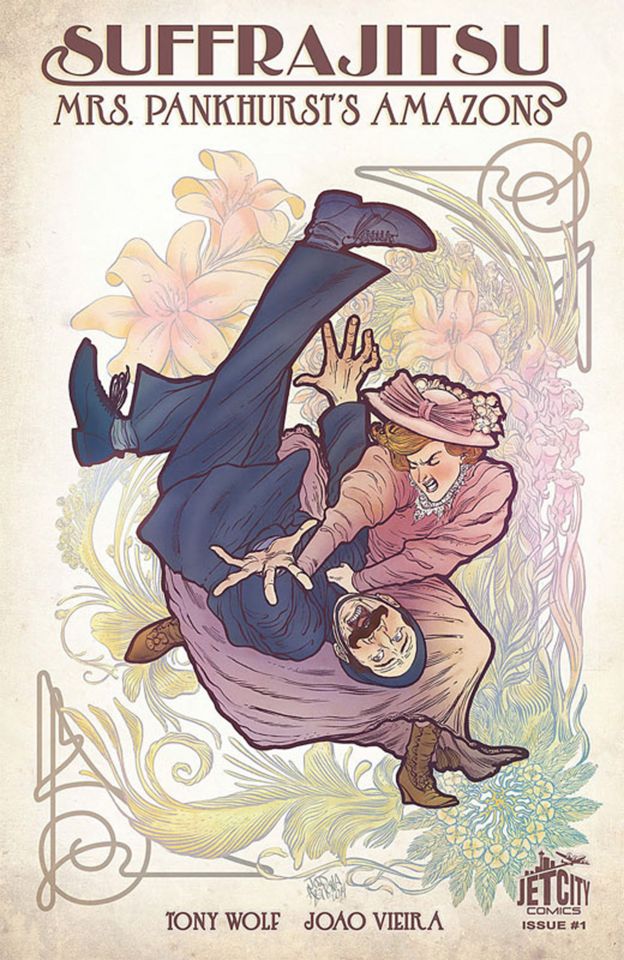

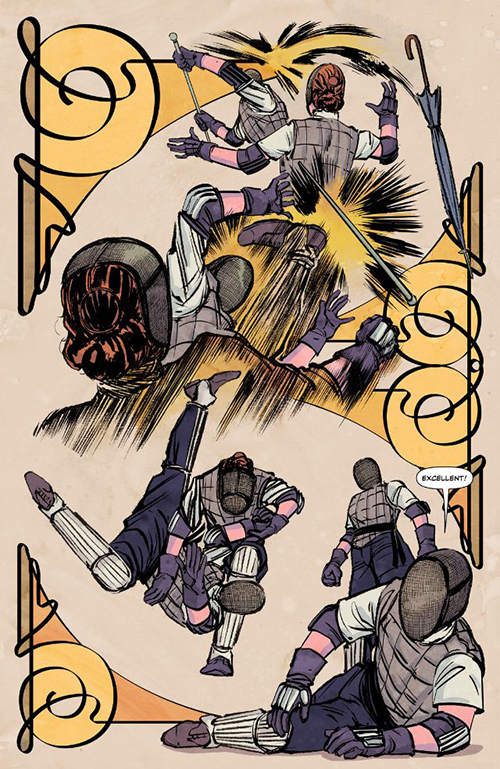

Another option for learning more about these “jiujitsuffragettes,” as dubbed by the press of the day (and having fun doing it), is the graphic novel trilogy, “SUFFRAJITSU: MRS. PANKHURST’S AMAZONS” (2015), written by Tony Wolf, with art by Joao Vieira.

Set in early 1914, at the height of the suffragette movement in London, SUFFRAJITSU introduces us to the Bartitsu-trained women who protect Emmeline Pankhurst, and two of their real-life instructors, Edith Garrud, the women’s jiujitsu instructor at the Bartitsu Club, and the mysterious Miss Sanderson, who was actually Marguerite Vigny, the wife of Pierre Vigny, the cane and savate instructor at the Bartitsu Club.

“The first part of the story is very closely based on real history,” says author Wolf, “as the Amazons engage in escalating confrontations with the police. The strategies of jiujitsu were seen as a metaphor for the womens’ fight to get the vote, and the Amazons served as symbols of women’s defiance against the state’s authority as well as functional bodyguards. Both sides were really engaged in an all-out, hearts-and-minds propaganda battle by that point.”

Wolf is a martial artist, martial arts scholar, fight choreographer and stuntman whose credits include developing the different styles used by the various races in Peter Jackson’s LORD OF THE RINGS trilogy (2001, 2002, 2003). He got his start in eastern styles such as Taekwondo, but became intrigued by the history of martial arts in Europe. His researches led him to Bartitsu, a hybrid style developed by E. W. Barton-Wright (hence the name), a British engineer who spent three years in Japan, which he introduced in London in 1898, according to Wolf.

“Bartitsu was an eccentric ‘mixed martial art‘ combining boxing, jiujitsu, kicking and the Vigny method of self-defense with a walking stick,” says Wolf. It is quite probably the source of Sherlock Holmes’ “Baritsu” style.

In about 2002 Wolf used what he calls “historical detective work and practical pressure-testing” to bring back the lost art of Bartitsu. “Reviving Bartitsu as a sort of gentlemanly Jeet Kune Do, or maybe ‘Edwardian Dog Brothers,’ has been my main martial arts interest since then,” he says.

Wolf’s first exposure to Mrs. Pankhurst’s Amazons happened much earlier, though.

“I remember first coming across an anecdote about the ‘jiujitsuffragettes’ in a martial arts history book when I was a teenager,” he says. “Apparently, young, middle-class London suffragettes would shinny down the drainpipes and sneak off to secret self-defense classes in the dead of night.”

An appealing image to a rebellious teen, but Wolf did not begin to study them in earnest until he was researching the history of Bartitsu. “I came across more and more information about the suffragette Amazons. Eventually I incorporated that information into some Bartitsu-themed books and a documentary I co-produced in 2010.”

Then well-known science fiction and fantasy author Neal Stephenson, a Bartitsu aficionado, approached Wolf to write the story of the Edwardian Amazons for Stephenson’s vast shared-world project, the Foreworld Saga.

“I think [Stephenson] was really taken by the idea of a group of bad-ass Edwardian ladies and wanted to see that happen somewhere in the Foreworld,” Wolf says.

With more experience in non-fiction than fiction, Wolf approached the project with some hesitation. “It was a bit of a leap of faith for Neal to get me involved in the Foreworld project,” Wolf says. “I’m very grateful that he did, though, because it was a blast to get to work creatively with all the jiujitsuffragette material I’d been gathering for years.”

The truth is almost as strange, though, and provides a fascinating glimpse into women in the martial arts in the early 20th century. A number of circumstances—some positive, some less so—had begun to open up the pursuit of martial arts to women.

“Women who wanted to learn jiujitsu weren’t typically considered to be less than ladylike,” Wolf says. “It dovetailed nicely with several other popular trends, including ‘physical culture’ or exercise training, which was generally looked on with good favor, and there was also a lot of popular enthusiasm for Japanese culture at the time.”

On a darker note, says Wolf, “There was a growing awareness of assaults in public spaces, on board trains, and so on, especially as more and more women went into employment and started to travel in cities without chaperones.”

It’s probable that both Marguerite Vigny and Edith Garrud developed new techniques for the women under their tutelage, says Wolf. “Madame Vigny’s system was a pragmatic adaptation of her husband’s method, based on using the umbrella or parasol as a combination of rapier and short spear,” he says, while the women learned some interesting and very effective techniques with Indian clubs, either from Garrud or through trial and error.

“There are very few specific records of how the clubs were used, but the Amazons did learn to target police constables’ helmets, because if the constables lost their helmets, they had to pay for them to be replaced,” Wolf says. Knocking a helmet off a bobby’s head generally sent him scrambling after.

The women also found a useful technique for dealing with the mounted police. “One of the suffragettes figured out that, if you struck a police horse on the back of its knee with an Indian club, the horse would sit down quickly and dump a mounted constable off its back. The horse wouldn’t be hurt, so that was a great counter-move.”

According to Wolf, the suffrage movement in the US did not employ similar tactics. “The US suffrage movement was nowhere near as radical as the suffragettes in the UK,” he says. By some accounts, the violence employed by the more radical suffragettes in London set their cause back by a few years. But following World War I the men of England realized that the women of England deserved a voice and a vote.

After all, there’s only so much you can say with your fists.

“Remember, remember, the 5th of November …”

The evening of November 5th marks the commemoration of Guy Fawkes Night in England and throughout parts of the British Commonwealth. Although originally framed as a celebration of the failure of the Gunpowder Plot conspiracy of 1605, the festival has, in more recent decades, taken on something more of an anarchic, anti-authoritarian tone. For many people, Guy Fawkes Night has become almost more a celebration, via fireworks, bonfires and even mass street protests, of the attempt to destroy the English House of Lords.

As such, it was fitting that Thursday, November 5th 2015 saw a salon commemorating the secret society of radical suffragettes who, circa 1913/14, employed incendiary means – including vandalism, bombs and arson – in their subversive campaign to win the right of women to vote in English elections.

Hosted by Suffrajitsu author Tony Wolf and facilitated by the Illinois Obscura Society, the Suffrajitsu Salon took place in the Victorian-themed Hutton Lounge at the Forteza Fitness and Martial Arts studio in Chicago’s Ravenswood neighborhood.

A capacity audience, some of whom arrived in suitably Victorian attire, enjoyed partaking of a variety of tasty teas and finger foods while perusing a gallery of framed pages from the Suffrajitsu graphic novels and a slideshow of rare suffragette photographs and cartoons.

Meanwhile, ragtime music and a large bouquet of green, white and purple flowers – the symbolic colors of the radical suffragette movement, representing hope, nobility and purity – further set the mood.

The first part of the lecture dealt with the historical origins and adventures of the suffragette “Amazon” Bodyguard team, including their training by Edith Garrud and anecdotes about some of their daring escapes, rescues and battles with the police.

After a short refreshment break, the second part of the presentation highlighted the recent trend towards celebrating the Amazons in fiction, such as the new Suffragette feature film and the Suffrajitsu graphic novels.

An enthusiastic question and answer session then segued into a demonstration of “suffrajitsu” self defense, in which a member of the Amazons – attired in an authentic, antique “physical culture” uniform – took on a fully uniformed, truncheon-wielding British police constable. The value of jiujitsu as a means of “victory by yielding” was displayed, as well as combat tricks with the Amazons’ signature weapon – the Indian club – and also means of self defense with an umbrella or parasol, in the fashion of “Miss Sanderson’s” unique system.

The evening salon was an unqualified success.

This new Atlas Obscura article by writer Tao Tao Holmes highlights both the Suffrajitsu graphic novels and the real history of the suffragette Amazons, including an interview with Suffrajitsu author Tony Wolf. Here’s an excerpt:

This new Atlas Obscura article by writer Tao Tao Holmes highlights both the Suffrajitsu graphic novels and the real history of the suffragette Amazons, including an interview with Suffrajitsu author Tony Wolf. Here’s an excerpt:

“Wolf describes himself as a ‘very staunchly feminist sort of guy,’ and while writing Suffrajitsu, he approached the women as a group of professionals, political radicals committed to an ideological goal. “The fact that they were female was third or fourth in the list of priorities in terms of how I wanted to present them,” he explains.

At the same time, he didn’t want it to be ‘women: good; men: bad.’ There were many men who very assiduously supported the radical suffrage movement to the point that they earned their own nickname: suffragents. Suffragents supported these women while they engaged in very aggressive, though non-violent civil disobedience. ‘These women were very careful and also very lucky that no one was physically harmed in their protests—even the extreme stuff like bombing,’ says Wolf.”