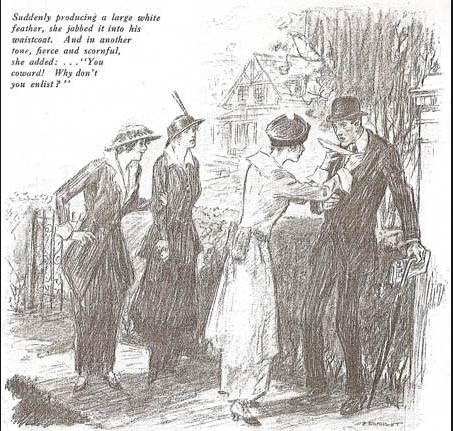

In the third book of the Suffrajitsu trilogy, Christabel Pankhurst is shown encouraging the women of England to hand white feathers to “every man you see who is not in uniform”. What was the meaning of this campaign, and why does Persephone Wright reject it?

In real history, the “White Feather” campaign was initiated during August of 1914 by Admiral Charles Fitzgerald and the author Mary Augusta Ward. Within the context of nationalistic fervor at the outbreak of the War, their plan was simple; in order to reduce “malingering”, which was the then-current term for avoiding military service, women would hand symbols of cowardice to young men in civilian clothes, with the object of humiliating them into joining the Army.

Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, who had by then suspended their “Votes for Women” campaign and thrown their efforts into supporting the government for the duration of the war effort, became enthusiastic proponents of conscription. Christabel went further, advocating internment for all members of “enemy races” in England. There is, however, very slight actual evidence linking either of them to the White Feather campaign, other than a paragraph in Sylvia Pankhurst’s 1931 suffragette memoir which conflated her mother’s and sister’s followers with that campaign.

Given that Sylvia had been bitterly estranged from her family, it seems not unlikely that this assertion was either vindictive or honestly mistaken; detailed archive searches have revealed no direct correlation between the WSPU and the White Feather Brigade.

It’s impossible to judge how effective the campaign actually was, but it quickly became highly controversial. Notably, members of the “Order of the White Feather” were criticized for indiscriminately targeting any man who was out of uniform, including those who were engaged in crucial public service occupations and those who had been honorably discharged from the Army due to injury or illness. The government responded by creating various lapel badges, including the “King and Country” and “Silver War” badges, to indicate that the wearer was not a malingerer.

Compounding the controversy, soldiers who were “at home” (on leave from active service) were also frequently handed white feathers if they chose not to wear their uniforms while in public. One such was Private Ernest Atkins who was on leave from the Western Front and who was presented with a white feather by a girl sitting behind him on a tram. He responded by slapping her with his pay book, saying: “Certainly I’ll take your feather back to the boys at Passchendaele. I’m in civvies because people think my uniform might be lousy, but if I had it on I wouldn’t be half as lousy as you.”

As the War dragged on and especially as news of the horrific conditions faced by soldiers filtered back to England, the White Feather campaign began to lose popular support.

Although the campaign was briefly revived during the Second World War, the effort was by then widely perceived to be in infamously bad taste.

In the fictional universe of Suffrajitsu, protagonist Persephone Wright rejects Christabel’s encouragement to support the White Feather campaign on ethical grounds, stating that “A man who’s been shamed into service isn’t a volunteer at all”. This is particularly significant in that Persephone had previously been among the most ardent supporters of Christabel’s “Votes for Women” movement during the pre-War period.