From Jiu-jitsu

“Suffragette Style”

By Lucy Addington (History Wardrobe)

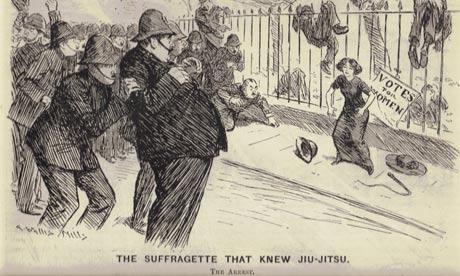

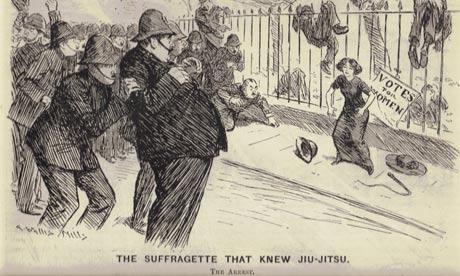

One Edwardian woman who certainly didn’t let fashion hobble her was martial arts expert Edith Garrud. Her ju-jitsu skills made a mockery of would-be muggers and over-assertive policemen alike. She kept wooden clubs in her hand-warming muff. If she sweetly dropped her handkerchief in the street it was as a prelude to a devastating bit of self-defence.

Undaunted by the contrast between the demands of appearance and the demand for political representation, both militant and non-violent suffragists learned to use their clothes as part of a series of battle tactics. For example, women who were dressed impeccably could pass without suspicion into public spaces or political meetings. Once in place they could whip chalk from their purses to scrawl slogans on pavements; they could pull chains from their handbags to secure themselves to railings, in order to have their say while someone searched for bolt-cutters. ‘Slasher’ Mary Richardson even concealed a small axe in her blouse sleeve, ready to attack Velasquez’s painting, the Rokeby Venus, at the National Gallery.

You can read the rest of this article on the intersection of suffragism and fashion via the Edwardian Promenade website.

Emy Godfrey interviewed re. the Jujitsuffragettes

Defence Against the “Hooligan”: Bartitsu Methods in London (1901)

An article by “S.L.B.” from “The Sketch”, April 10, 1901:

Last year, a very interesting exhibition of self defence was given at St. James’s Hall, and was the subject of prolonged discussion by many of the people present. Mr. Edward Barton-Wright, who gave the demonstration, was honoured with an invitation to repeat it before the Prince of Wales, but he met with a bicycle accident and the exhibition became impossible. It may be that the style of self-defence introduced to public notice would have failed to attract attention by reason of its novelty alone, but Mr. Barton-Wright had not mastered it without the firm intent to give it a fair chance before the public. He proceeded to found a Club at 67b, Shaftesbury Avenue, where physical culture may be studied under Professors of all nationalities, some of the best of the world’s athletes and sportsmen being engaged as instructors. To-day the work is in full swing, stimulated by the uprising of the “hooligan”.

In his early days, Mr. Barton-Wright was an engineer, and his duties took him into strange lands and among ill-disposed people. He had to go slowly, and to learn that the knowledge of boxing under the Queensberry rules, his sole accomplishment then among the arts of self-defence, is of little or no use against men who attack their opponents with feet as well as hands, from below the belt as well as above it, from the back as well as face-to-face, and with bludgeons, life-preservers, knives and other persuasive weapons. The straightforward stroke that, catching the ruffian upon the “point” or “mark”, disables him from further attempts, is of little or no good when it cannot be delivered, and in every city he visited the young engineer found more and more to learn.

Soon he was seized with the bright idea of combining the self-defence of all nations into a system that, when properly acquired, should enable a man to defy anything but firearms or a sudden stab in the dark.

The chief point to bear in mind was that an adequate system of defence must be able to meet any form of attack; the man who endeavours to disable you by kicking you in the stomach is entitled to as much respect and consideration as he who strives to garrote you, or to try the relative resisting powers of a loaded stick and your skull.

The Bartitsu Club, through its Professors, over whom Mr. Barton-Wright keeps an admonishing eye, guarantees you against all danger. In one corner is M. Vigny, the World’s Champion with the single-stick: the Champion who is the acknowledged master of savate trains his pupils in another. He could kill you and twenty like you if he so desired in the interval between breakfast and lunch – but, as a matter of fact, he never does. He leads you gently on with gloves and single-stick, through the mazes of the arts, until, at last, with your trained eye and supple muscles, no unskilled brute force can put you out, literally or metaphorically.

In another part of the Club are more Champions, this time from far Japan, where self-defence is taken far more seriously than here. The Champion Wrestler of Osaka, or one of the shining lights among the trainers for the Tokio police, dressed in the picturesque garb of his corner of the Far East, will teach you once more of how little you know of the muscles that keep you perpendicular, and of the startling effects of sudden leverage properly applied. The Japanese Champions are terribly strong and powerful; at a private rehearsal of their work, given some two months ago on the Alhambra stage, I saw a little Jap. who is about five feet nothing in height and eight stone in weight, do just what he liked with a strong North of England wrestler more than six feet high, broad, muscular and confident. The little one ended by putting his opponent gently on his back, and the big one looked as if he did not know how it was done.

There is no form of grip that the Japanese jujitsu work does not meet and foil, and in Japan a policeman learns the jujitsu wrestling as part of his equipment for active service. One of the Club trainers was professionally engaged to teach the police in Japan before he came to England to serve under Mr. Barton-Wright.

When you have mastered the various branches of the work done at the Club, which includes a system of physical drill taught by another Champion, this time from Switzerland, the world is before you, even though a “Hooligan” be behind you. You are not only safe from attack, you can do just what you like with the attacking party. He is as helpless in your well-trained hands as a railway-engine in the hands of its driver. The “Hooligan” does not understand the principles on which he works; you do, and, if it pleases you to make his machinery ineffective for further assaults upon unoffending citizens, you can do so in a way that cannot be believed until it is seen. No part of South London need have terrors for you; Menilmontant, La Vilette and the shadier side of the Bois are as safe for you in Paris as the Place de l’Opera. I find myself wishing that the Bartitsu Club had been in Shaftesbury Avenue as recently as some five or six years ago, when shortly after midnight the slums of Soho would send forth ruffians at whose approach wise men sought the light.

The work of the Club makes a strong appeal to Englishmen, because they are naturally of an adventurous disposition and have a great aversion to the use of any but natural weapons of defence in the brawls that they are bound to encounter now and again. There is a keen pleasure in being able to turn the tables on a man who tries to assault us suddenly and by means that he relies upon to give him an unfair advantage. I am well assured that a few of Mr. Barton-Wright’s pupils sent into a district infested by “Hooligans” would do more to bring about law and order than a dozen casual arrests followed by committal with hard labour, with or without the “cat”. And there is an element of sport in the Bartitsu method that should appeal to any “Hooligan” with a sense of humour.

Neal Stephenson foreshadows “Suffrajitsu”

An excerpt from an interview by Douglas Wolk for the io9 website on May 30, 2012:

I ask Stephenson about the cane-fighting subgroup that drew Greg and Erik Bear into the project, and he’s off into explanatory mode again. (I’m not complaining. I could listen to Neal Stephenson explain stuff all day.) “It’s an interesting thing,” Stephenson says, “because from a distance 19th-century martial arts looks kind of dorky — it looks like Monty Python. It ties into everything we believe about the Victorians: that they were out of touch with their bodies, that they didn’t really understand medicine very well, and that they were uncomfortable with physical activities. But once you get into it, you find that these people really knew what they were doing in terms of physical culture, in terms of self-defense. Victorians were really serious about staying fit.

Part of what makes this an interesting story is how, in the 19th century, jiujitsu was adopted by women. This guy Barton-Wright brought jiujitsu to London. He came back from Japan and created a club called the Bartitsu Club. He taught the mixed martial art of jiujitsu, bare-knuckle fighting, savate, stick fighting and a few other things. He brought in a couple of teachers from Japan, and would take them around the music halls—have them challenge huge, burly guys and throw them around. This had an unintentional side effect that suffragettes would see these performances, and decide they wanted to learn self-defense: ‘I want to defeat a man!’ Jiujitsu as a ‘husband-tamer’!

We want to do a side-story quest thing about the jiujitsu suffragettes. The image that we’re all dying to get into a full-page spread in a comic book is this lineup of Edwardian women with the flowered hats and the long skirts and the bustles, and they’re all walking eight abreast down a London street, swaggering toward the camera and approaching a bunch of bobbies… if we could get that image in some medium, that would be a good thing.”

“Edith Garrud: a public vote for the suffragette who taught martial arts” (2012)

Click here to read journalist Rachel Williams’ article for The Guardian on Suffragette jiujitsu trainer Edith Garrud, including quotes from Tony Wolf.

The extraordinary Toupie Lowther

May “Toupie” Lowther (1874-1944) was a woman of many parts. Born into a very wealthy family, she was educated in France and returned to England as a fluent French speaker, an excellent singer, skilled composer and all-around athlete who quickly made names for herself in both competitive tennis and foil fencing.

If Miss Toupee (sic) Lowther had not devoted most of her leisure to sport — sport of a strenuous, masculine type — one could almost picture her leading a public movement in favour of “Woman’s Rights.” For she is essentially a lady of strong personality, destined to command, and her knowledge of men and women is so wide, her disregard of petty restrictions so pronounced, that apparently nothing would stop her if she once made up her mind publicly to support a policy of emancipation.

In the latter connection, her father, Captain William Francis Lowther, once challenged Captain Alfred Hutton, who was perhaps the most prominent and influential fencing master in England, to bout with his daughter. Although nothing came of the challenge, which may well have been issued partly in fun, a commentator noted that:

As all the world knows, (Toupie) is one of the most brilliant lady fencers in Europe. Coming from a stock of vigorous patriots who have fought their country’s battles at the point of the sword, she was early trained in the use of the rapier and the sword-stick, and, possessed of a lithe and hardy frame, it is small wonder that, at the age of eight she could engage in a fencing-bout with her elders with all the confidence of an expert. Fencing is not an art for namby-pamby girls or, indeed, for any girl who does not command more than the average amount of spirit and pluck, and Miss Lowther is, above all, a woman of indomitable nerve.

Her other sporting enthusiasms included driving, motorcycling, weightlifting and jiujitsu, which she pursued with sufficient enthusiasm that one writer worried that it might interfere with her fencing.

With the outbreak of the First World War Toupie became one of the organisers of an all-women team of ambulance drivers who undertook many dangerous missions to transport wounded soldiers near the front lines of battle in Compiègne, France. For this service she was awarded the Croix de Guerre in 1918.

Toupie was a friend of writer Radclyffe Hall and her partner, sculptor Una Troubridge, until after the publication of Hall’s controversial novel The Well of Loneliness in 1928. The novel’s female protagonist, Stephen Gordon, was probably based to a large extent on Toupie Lowther, and this seems to have caused a rift in the friendship. It has been speculated that Toupie may have objected to having been publicly “outed” as a lesbian and transvestite via the Gordon character, although her sexual orientation seems to have been no secret among her family and friends.

For much more detail on Toupie’s life and adventures, please see the excellent biographical website Toupie Lowther – Her Life – A New Assessment.

Toupie Lowther is also a supporting character in the Suffrajitsu graphic novel trilogy, in which she serves as Suffragette leader Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst’s chauffeur/getaway driver and as a member of her personal bodyguard of women.

“I am a woman, but no weakling” – Judith Lee, lady detective

He stopped – there was silence. The bell rang again. I was just about to suggest again that he should go and see who was at the outer door when – he leapt at me. And I was unprepared. He had me by the throat before I had even realised that danger threatened.

I am a women, but no weakling. I have always felt it my duty to keep my body in proper condition, trying to learn all that physical culture can teach me. I only recently had been having lessons in jiu-jitsu – the Japanese art of self defence. I had been diligently practicing a trick which was intended to be used when a frontal attack was made upon the throat. Even as, I dare say, he was thinking that I was already as good as done for, I tried that trick. His fingers released my throat and he was on the floor without, I fancy, understanding how he got there. I doubt if there ever was a more amazed man. When he began to realise what had happened he gasped up at me – he was still on the floor – “You … you …”

The above is quoted from the short story Mandragora, part of the Judith Lee detective series written between 1912-16 by Richard Marsh. Among the first protagonists of the still very popular lady detective genre, Judith Lee brought several unusual talents to her role as an amateur sleuth, including an almost uncanny ability to read lips and a willingness to physically apprehend evil-doers, thanks to her training in physical culture and jiujitsu. Certainly, she was among the first heroines in Western literature to have studied Eastern martial arts.

Isolda cried, with what he probably meant to be crushing dignity:

“Brayshaw, put this woman outside at once!”

The command seemed to be addressed to the barrel-shaped person. There was dignity neither in the manner of his approach nor in the words he used.

“Now, young woman, out you go! We’ve seen your sort before. We want none of your nonsense here! Not another word – outside! I don’t want to touch you, but I shan’t hesitate to do so if you make me.”

I smiled at the barrel-shaped man. The idea of such a creature putting me out of the room was really too funny.

“I will recommend you, Mr. Brayshaw, not to touch me, unless you wish to discover what an extremely ugly customer a woman can be.”

He tried to touch me, stretching out his hand with, I fancy, the intention of taking me by the shoulder. I am quite sure that, before he knew what had struck him, he was on his back on the floor.

“If you will be advised by me, you will allow me to make the remarks that I intend to make without any interruption; because, in any case, I intend to make them.” –

– Richard Marsh, Isolda

Several of Judith’s original (circa 1914) adventures are linked to from the Bunburyist website. She is also a supporting character in the Suffrajitsu graphic novel trilogy and you can read about her first encounter with the Amazons here: Judith Lee – her new and wonderful detective feats – The Wrestler and the Diamond Ring.

Flossie Le Mar, “the World’s Famous Ju-jitsu Girl”

Florence “Flossie” Le Mar was a pioneering advocate of jujitsu as feminist self defence.

Flossie and her husband, professional wrestler and showman Joe Gardiner, toured vaudeville theatres throughout New Zealand prior to the First World War. Their signature act showed audiences how a Lady might fell an aggressive Hooligan in any number of ways. According to a 1913 poem promoting the vaudeville act:

In ‘The Hooligan and Lady’, they are smart, clean, clever, straight.

No act in this world is better – fast, and strictly up-to-date.

This act[’s] a small-sized drama – constructed round Jitsu

A Japanese discovery, wherein they show to you,

How it’s possible for a lady, when molested by a cad,

Maybe tackled by a robber, in fact, any man that’s bad,

Can hold her own against him and quickly put him through,

When she knows the locks and holds – pertaining to the art Jitsu.

So clever is the lady that when the tough with pistol, knife

And bludgeon tries to rough her and mayhap take her life,

Like lightning-flash she meets him and quickly stays his hand,

By tumbling him hard earthwards – I tell you it is grand –

And proves to me and all here what women folk can do

When attacked, if they but study Miss Le Mar at Ju Jitsu.

These techniques were also explained and illustrated in Flossie’s book, The Life and Adventures of Miss Florence Le Mar, the World’s Famous Ju-Jitsu Girl, which is undoubtedly one of the rarest and strangest self defence manuals ever written.

In addition to jujitsu lessons, Flossie’s book offered a great deal of feminist polemic and a series of very tall tales describing her hair-raising adventures as the “World’s Famous Ju-Jitsu Girl”, taking on desperadoes including opium smugglers in Sydney, crooked gamblers in New York City and an English “lunatic” who believed he was a bear. In each story, Flossie the Jujitsu Girl defends the weak and innocent and punishes villains through her mastery of the martial arts.

Though not without charm, these short stories have the sharp corners and hard edges typical of early 20th century dime novels. They are also undeniably theatrical and, in combination with Flossie’s biography and her fierce feminism, inspired the production of a play, The Hooligan and the Lady, which was a hit at the 2011 New Zealand Fringe Festival.

Hooligan vs. Lady from Nick McHugh on Vimeo.

A fight scene/Edwardian-era self defence demonstration from The Hooligan and the Lady.

Flossie’s adventurous “Ju-Jitsu Girl” persona is also among the key characters in the upcoming graphic novel trilogy Suffrajitsu. In the story, Flossie Le Mar is a member of a secret society of radical suffragettes known as the Amazons, who protect the leaders of their movement from arrest and assault.