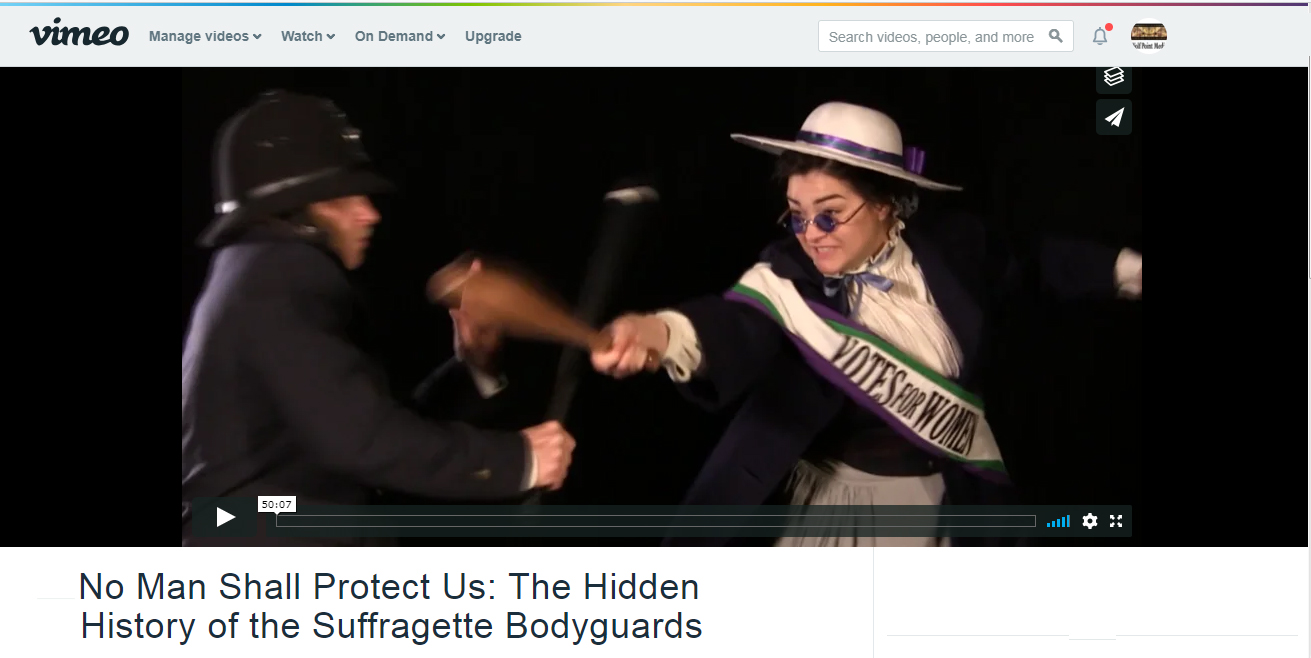

For a number of years, the 1982 docudrama The Year of the Bodyguard, directed by Noel Burch, was one of the sasquatches of Edwardian antagonistics research. There was tantalising evidence that it existed somewhere, but it proved frustratingly difficult to track down.

In early 2013 we (finally!) had the opportunity to watch the telefilm, which was originally broadcast as part of a British Channel 4 documentary series called The 11th Hour. What follows is not a review, but a comprehensive summary of the film, highlighting those aspects most likely to be of interest to readers of this website.

The film opens with a shot of a chair, upon which rest a red Edwardian-style jujutsu gi (training uniform), an Indian club and a short whip – weapons associated with the militant Suffragettes. In voiceover, an actress representing Edith Garrud briefly quotes the advice given to her by Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankurst – “Speak, and I think that we shall understand”.

Cut to the narration of an eyewitness to police brutality against a Suffragette protestor during the infamous “Black Friday” riots of 18 November, 1910, as the camera very slowly pans in on the face of a woman who has fallen to the pavement:

There follows some early newsreel footage of the riot itself; lines of police, a vast, milling crowd of behatted Londoners pressing around a small collection of suffrage banners off in the distance.

Next, there is a re-enactment of the Women’s Social and Political Union’s “Votes for Women” exhibition at Prince’s Skating Rink in Knightsbridge, in which a mock-up of the relatively opulent, large cell afforded to recognised political prisoners is contrasted with the cramped, miserable cell of an imprisoned Suffragette. We then watch a re-enactment of the forced feeding of a Suffragette on hunger strike.

A fashionable shop window is smashed by an unseen militant Suffragette protestor crying “Votes for women!”, and next we see the protestors, having barely out-run the police, escaping into Edith Garrud’s jiujitsu studio. They quickly hide their weapons of vandalism – hammers and stones – and street clothes in a trap-door hidden under the tatami mats, and by the time the police arrive, they appear to be a group of young women innocently practicing jiujitsu.

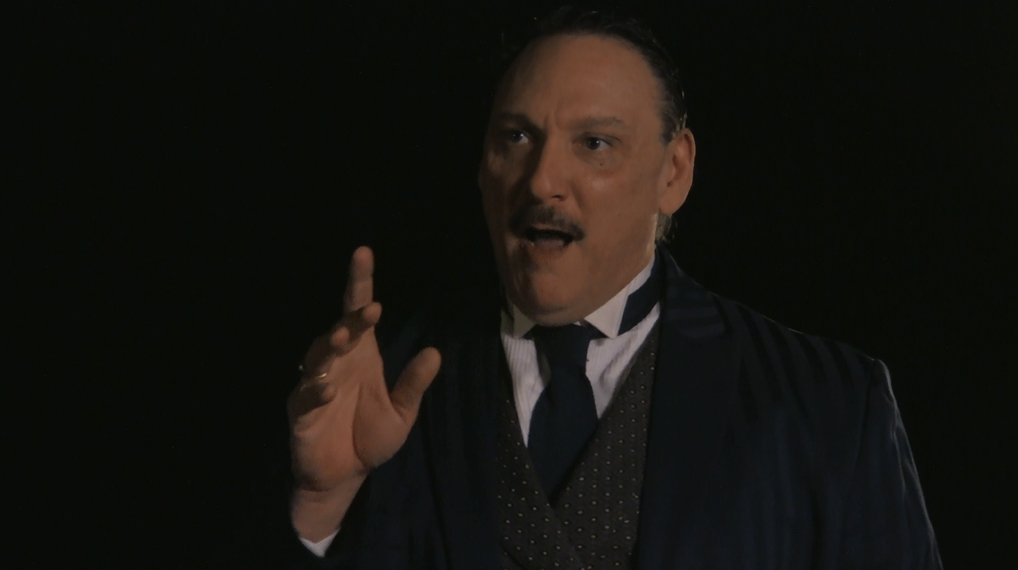

Next, an actor portraying G.K. Chesterton delivers a monologue to the camera, making the point that a woman’s deltoid muscles are the least thing a man has to fear from her. This is followed by a startling scene of modern (1980s) domestic violence.

Returning to the Edwardian era, we witness another common form of Suffragette protest by vandalism, as a woman pours a liquid accelerant into an iron post-box and incinerates the mail within. A female narrator quotes Christabel Pankhurst on the relative moralities of different types of violent action.

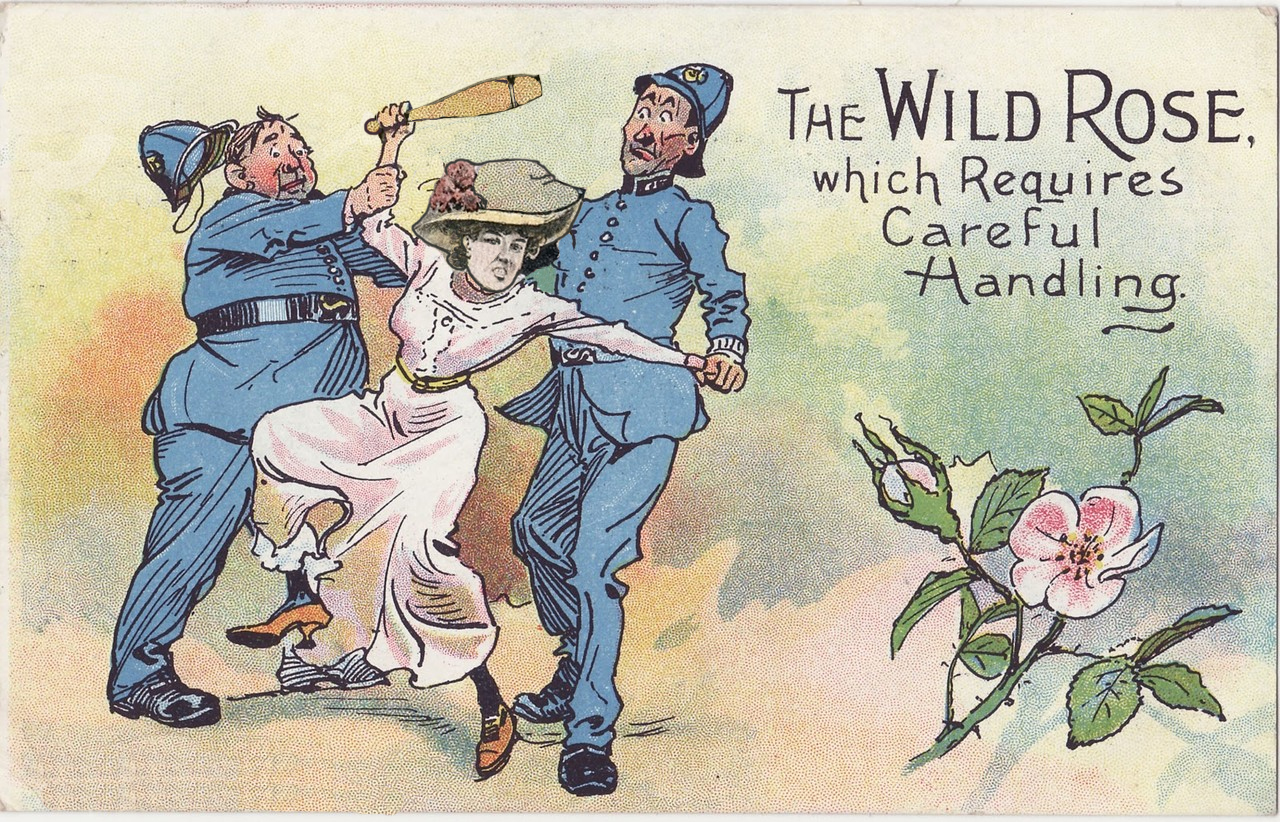

This is followed by a documentary photo-montage of militants being arrested and disorder in the streets of London, while a male narrator explains the doctrine of state-sanctioned physical force behind the rule of law, also suggesting that while physical force is a male domain, the law drew equally from moral force, which is associated with women; “let the men make the laws, and we (women) will make the men.”

An actress portraying a working-class suffragist from Lancashire delivers a speech to the camera in the style of a 1980s television interview, arguing that the undignified protests of middle- and upper-class women who “kick, shriek, bite and spit” were driving her peers away from public political action.

There follows a long, static shot, rather in the manner of early silent film, showing a performance of the George Bernard Shaw play, Androcles and the Lion, which is disrupted by a loud argument on the suffrage question between members of the audience. Three of the actors on stage eventually break the fourth wall and applaud the pro-suffrage position.

The next shot is of a black and white television set which is showing an actress playing the elderly Edith Garrud circa 1967. She describes her first meeting with Emmeline Pankhurst, which took place at a jiujitsu display she was giving in the early 1900s.

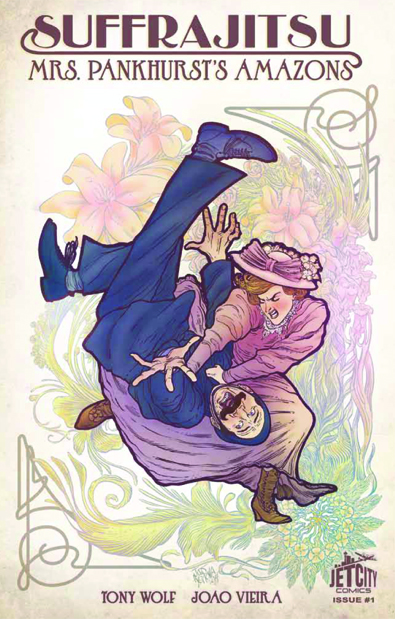

We then segue to another actress playing Edith at the time of that display, lecturing on jiujitsu and demonstrating several holds and throws on a man wearing a police uniform.

We shift to September of 1913, as two plain-clothes police officers climb a ladder outside a building to secretly observe a Bodyguard jujitsu training session through a skylight.

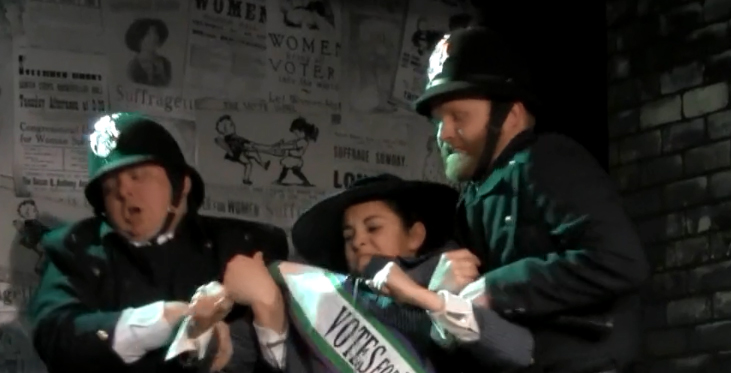

One of the women spots them and, after some confusion, organiser Gertrude Harding orders the trainees to leave one at a time and not to allow themselves to be followed home. The camera follows one of the women as she confronts a detective in the street and proposes a game of wits; if she is able to lose him, she will win. They walk off into the darkness.

A narrator quoting Christabel Pankhurst describes the formation of the Bodyguard and the power of women to terrorise men, over a montage of photographs and early film footage showing Suffragettes in prison, practicing jiujitsu and protesting, “divinely discontented, divinely impatient and divinely brave”.

Next there is a re-enactment of three militant Suffragettes harassing Prime Minister Asquith during a motoring trip through a Scottish forest. The women rush out from hiding and stop his car, then attack Asquith and his companions with flour-bombs and horse-whips, crying “votes for women!” and “Asquith out!”

The next sequence quotes a speech by Sylvia Pankhurst, who was concerned with organising political protest among the working classes of London’s East End, urging her followers to learn jiujitsu and to bring sticks to their protests. “There is no use talking. We have got to really fight.” This is followed by a stylised, slow motion scene in which the young Edith Garrud, wielding an Indian club as a weapon, defeats two male attackers in front of a flickering projection of a suffrage rally.

This scene is interrupted by the Year of the Bodyguard director, Noel Burch, who asks the actress playing Edith to demonstrate one of her jujitsu locks for him. She asks why and the scene freezes momentarily.

There follows a humourous scene in which a large, but bruised and dishevelled c1913 police constable is interviewed by a female reporter, ostensibly in the aftermath of an encounter with the Bodyguard. He abashedly admits that he was hit by a woman, claims that he doesn’t know whether he supports the right of women to vote in elections, and ends up distractedly trying to re-attach his right sleeve, which has been partially torn off during the affray.

The film then takes a much more serious turn, with slow-motion archival footage of the Suffragette protestor Emily Wilding Davison running into the midst of the Derby Day horse race of 1913 and being trampled by the King’s horse, Anmer. Both woman and horse somersault through the air after the impact, and then the crowd surges on to the racetrack to help; the horse survived and Emily Davison became the first Suffragette martyr.

In a satirical scene, an actor in modern dress playing a psychiatrist offers the opinion that Wilding was a masochist and a “hysteric”.

The final scenes show a group of women training in a contemporary (early 1980s) self defence class, followed by a series of interviews with the trainees about the value of learning self defence and the politics of inter-gender violence. Following a short scene in which a woman is shown defending herself against an attacker in a busy London street, a title card describes the impact of the First World War on the suffrage movement, as Mrs. Pankhurst suspended the “Votes for Women” campaign and organised many of her followers to support the government during the war effort, which prompted the granting of the vote to women over the age of 30 on 11 January, 1918.