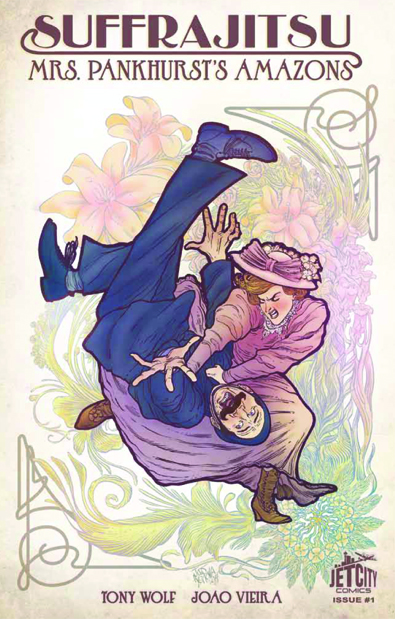

We’re pleased to be able to present this December, 2013 interview with Tony Wolf, the author of the upcoming graphic novel series Suffrajitsu. Tony’s books will be part of the Foreworld Saga created by Neal Stephenson, Mark Teppo and others.

Both Bartitsu and the elite Bodyguard Society of the British Suffragettes play key roles in the Suffrajitsu trilogy, which will be published by Jet City Comics.

SOME LIGHT SPOILERS AHEAD …

Q – Tony, this is your first graphic novel, but not your first book – how did you come to be asked to write this series, and did your prior work have anything to do with it?

TW – I’ve written and edited quite a lot of historical non-fiction, mostly on esoteric Victorian-era martial arts topics – that’s been my major research interest over the past fifteen years or so. The project most directly relevant to the graphic novel was a children’s history book called Edith Garrud – the Suffragette that knew Jujitsu, which I wrote in 2009.

I actually kind of moved sideways into scripting Suffrajitsu out of my participation in brainstorming for another Foreworld project. I think it was in late 2011 that Neal (Stephenson) first mentioned the graphic novel deal with Amazon and asked me to contribute something on the theme of the Suffragette bodyguards.

Q – How did the writing process compare to your prior books/anthologies?

TW – It was a joy in that after so many years of antiquarian research into these themes, this was my first real opportunity to get creative with them. There was this sense of a dam, not completely bursting, but definitely exploding at certain key points.

Q – Tell us what you can about the series in your own words.

TW – Well, the events of the first book are based very closely on historical reports of actual incidents, although it’s become a kind of “secret history” in that the Suffragette Bodyguards were almost completely forgotten after the First World War.

We’re introduced to the main characters and their situation as political radicals – outlaws, really – in 1914 London. By that time, both in real history and in my story, the battle for women’s rights had reached a boiling point. The suffragettes’ protests and the government’s reprisals were becoming more and more extreme. Persephone Wright is the leader of a secret society of women known as the Amazons, who are sworn to protect their leaders, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, from arrest and assault.

Q – And that really happened, correct?

TW – Persephone is a fictional character but yes, there really was a secret bodyguard society attached to the militant suffragette movement.

The Amazons are Bartitsu-trained bodyguards and insurgents, saboteurs – the most radical of the radicals. They’re all under constant threat of imprisonment and worse.

Something happens in the first book that is a major divergence from actual history and that’s what spins the story off into the alternate timeline of the Foreworld universe.

Q – Where did you get the inspiration for the storyline when it veers away from history?

TW – It was clear that it would take a dramatic event to move the story into the events of the second book … I can’t say much more than that!

Q – But I understand that both historical and fictional characters appear as principal figures?

TW – Yes indeed. Many of the characters, like Edward Barton-Wright, are lightly fictionalised versions of their historical selves – as well as I “know” them from research – transposed into the Foreworld timeline.

The real Amazons were literally a secret society and even now we only know the names of a few of the actual women who were involved. I took that as artistic licence to bring in several “ringers” from both fiction and history. Judith Lee, for example, was the protagonist of Richard Marsh’s popular series of “lady detective” short stories during the early 20th century. Flossie le Mar, another member of my imaginary Amazons team, was a historically real person – she was a pioneer of women’s self defence in New Zealand – but she also had a sort of dime novel “alter ego” as the adventurous “Ju-jitsu Girl”, so it was a very easy decision to make her one of the Amazons.

Q – Are any of them purely invented and, if so, what purposes do those characters fulfill?

TW – The only major character that I entirely invented is Persephone Wright herself. Even though she was partly inspired by several real suffragettes, including Gert Harding and Elizabeth Robins, I wanted the freedom of creating an original protagonist.

Persi actually surprised me several times – she’s much more of a Bohemian than I’d first imagined, and there’s a fascinating tension between her free-thinking inclinations and her disciplined drive to protect people at any cost. She’s roughly half hippie and half samurai. I think she’d often really rather be off partying at the Moulin Rouge or writing poetry in a Greenwich Village tea-room, but damn it, she has her duties.

Q – What do you hope will come out of the series?

TW – My dream scenario is that it will inspire readers to create their own stories set in the world of the Amazons; anything beyond that will be gravy.

Q – Do you have any trepidation about being a male author writing a graphic novel with mostly female protagonists?

TW – No, but I’m aware that some readers will have me under the microscope on that account. My only agenda is that I think it’s amazing that a secret society of female bodyguards defied their government, putting their physical safety and freedom on the line over and over again, to secure the right to participate as equals in a democracy. Their story was absolutely begging to be told in some medium or other and I’m honoured to have been given that chance.

One thing I tried hard to do, allowing that this is a work of alternate history fiction, was to portray the Amazons as fallible human beings. For example, some of them have habits and attitudes that have become deeply unfashionable over the past century. They’re also more-or-less outlaws and have that very specific ethical/political perspective of the end sometimes justifying the means; none of them are entirely “wholesome”. Actually, none of them are “entirely” anything. As far as I’m concerned, their foibles, ambiguities and unique perspectives make them worthwhile as characters.

Likewise, I’ve been careful to try to convey that it wasn’t just a simple matter of “righteous women versus oppressive men”. Historically, many men energetically supported women’s suffrage – the newspapers nicknamed them “suffragents” – and many women were vehemently opposed to it, especially as the cause became more radical.

Q – Would you have been a suffragent?

TW – Absolutely!

Q – How has the process of working on Suffrajitsu been for you?

TW – It’s been an intensive, ground-up self-education in the nuts and bolts of scripting a graphic novel. You’re constantly playing Tetris with the plot and dialogue to work everything in within strict boundaries – only so many words to a speech balloon, so many speech balloons or captions to a panel, panels to page and so-on. My editors and João Vieira, the artist, have been very patient with me as I’ve worked those things out.

Obviously, there’s a huge amount of sub-plot and back-story etc. that I simply couldn’t fit in. We’re currently developing the Suffrajitsu.com website for the series, which will help with all of that and hopefully allow for some ongoing, active engagement with readers. There will also be some free short stories to whet readers’ appetites for further Suffragette Amazon adventures.

Q – Do you have a favourite character or a favourite moment in the series?

TW – Oh, that’s hard … my inner 13-year-old has a real weakness for cool badasses so perhaps the mysterious Miss Sanderson is a favourite in that sense. Similarly, (name of the villain redacted because spoilers) … the fact that he was actually a real person is somehow both appalling and deeply satisfying. If he hadn’t really existed, I would have had to invent him.

I do have a favourite moment, come to think of it, but that comes late in the third book. I haven’t even seen the art for that sequence yet, so it’ll have to wait for a future interview!

Q – Finally, then, when will the stories be released?

TW – We don’t have definite dates yet, but the website will probably be officially launched in November and the first book is scheduled to be published during early 2015. All of the stories will be issued first as individual e-books via Kindle, then later together with some bonus material as a printed collector’s edition.

Q – That’s something to look forward to! Thanks for your time.

TW – Thank you!