“Welcome to New York!” went up the cry from the docks, and I gratefully returned my feet to terra firma after a choppy week-long Atlantic crossing aboard the R.M.S. Olympic; unknowing that, within a few days, I should be plunged into one of my very strangest adventures.

In clearing customs, I enjoyed the novelty of being interrogated by a charming young agent whose Brooklyn accent was so impenetrable that I resorted to reading his lips. We shared a joke about my unusually sturdy umbrella, he stamped my passport and that was that. After being formally admitted to the United States, I made my way by taxi-cab to the Gilsey House at 3671 Broadway. This eight-story hotel was to be my base for the next seven days, during which time I would deliver a lecture at an international symposium, convened by the New York State School for the Deaf.

I am, as you may already know, a teacher of the deaf by profession. It affords me great satisfaction as well the opportunity to travel widely and to meet people from all walks of life. Sometimes, of course, the new people whom one meets are not so very nice, and then I feel morally bound to intervene, especially when not-so-very-nice people interfere with the lives of the blameless.

People have called me a detective, and I suppose that is accurate as far as it goes. More recently, some have also called me a suffragette, which is a name I bear proudly, especially when it is offered as an insult. Precious few, however, know that I am a member of Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst’s clandestine vanguard, popularly known as the “Amazons”.

It was due to this association, incidentally, that I now habitually carry the umbrella that had amused the young customs agent. We call them “Sanderson specials” and they are cleverly contrived of spring steel, baleen and malacca cane. To the casual gaze, these are the same staid brollies that protect all Londoners in drizzle and downpour alike, but those in the know wield them as combination bayonets, rapiers, daggers and maces, as may befit the urgent needs of a given moment.

Needless to say, this is not something that one explains to American customs men, no matter how charming.

![]()

The next morning I found that I had over-slept and so quickly repaired downstairs to the busy dining room. There I was presented with a breakfast of fruit salad and crumpets, which my hosts, the Washingtons, referred to as “English muffins” and insisted on smothering with butter and a treacly syrup called “molasses”. I did not ask whether this was a local delicacy or simply what they assumed an exotic visitor would enjoy.

Because I am Chinese to outward appearance but speak English with a pronounced Kensington accent, Americans are often a little unsure of what to offer in these situations. In any case, I enjoyed the fruit and the treacle crumpets washed down tolerably well with some milky mint tea.

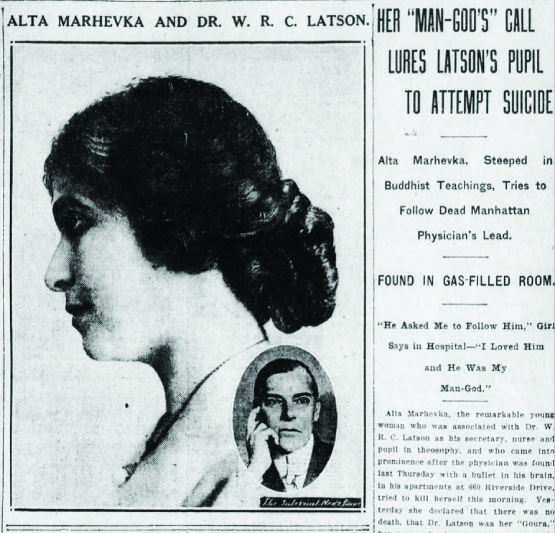

As I ate, I was joined at the table by a slender, dark-haired girl a few years younger than myself, who introduced herself as Alta Marhevka. It transpired that she lived in the hotel, in the room right next to mine, and was employed at some kind of medical clinic on Riverside Drive.

Miss Marhevka quickly impressed me as being very bright indeed, and also very intense, her large, dark brown eyes gleaming as she described her interest in Chinese philosophies. Candidly, I felt it was a bit early in the day for such earnest conversation, but I indulged her with some Taoist anecdotes, which seemed to please her very much.

Just then a large guest – German, from her bearing and accent – accidentally bumped into our table, causing some hot tea to spill into Miss Marhevka’s lap. The German lady apologised profusely and petted at her, but Miss Marhevka graciously waved her away and set about mopping up the tea with her napkin.

“You poor dear – doesn’t that hurt?” I asked. She replied simply, but with an enigmatically rueful smile, “I would rather be abused than pitied, Miss Lee.”

“A curious girl,” I thought as I bade her farewell, but of course I’m sure I leave the same impression upon many people. I retrieved my Sanderson special from the umbrella-stand and sallied forth for a day of sight-seeing.

![]()

It was later than I’d intended when I finally returned to the Gilsey House, for I had been rather turned around after dinner at the White Horse in Greenwich Village and had walked for a considerable distance in the wrong direction. New York City streets are so long and so straight, and I confess that the grid pattern took more getting used to that I might have thought.

I made my way upstairs to the third floor and was fiddling with my room key when I smelt the unmistakable odour of gas. A cold chill ran down my spine as I realised that the smell was emanating from under the door of Room 303 – Miss Marhevka’s room. I knocked on her door, then called out her name, then pounded and called again, but there was no response. Meanwhile, I fancied that the smell was getting stronger and that, when I placed my ear to the keyhole, I could hear the faint hiss of gas jets.

Fearing the worst, I set my right foot back and then thrust it with all my strength at the door. I was rewarded with a cracking noise, but the lock held fast. Two more savate kicks and the door burst inwards, followed instantly by an invisible wash of escaping gas that was almost enough to send me staggering.

The miasma dissipated in moments, so I took a deep breath and sprang forth into the moonlit room, beholding Miss Marhevka reeling to her feet from the couch. The grey carpet was littered with scraps of notepaper, dozens upon dozens of them, and all three gas lamps had been torn from the walls, their jets hissing like cobras. The expression on Miss Marhevka’s face was one of stricken fury.

“No!” she cried, her voice harshly strained. Her hands sprang up and curled into claws. “No, get out, get out of here!” Just then she was overcome by a bout of violent coughing, swayed and nearly swooned.

I would not waste breath on arguing and ran to her, seizing her sleeve so as to pull her out of that gas chamber. But she would have none of that, slipping beneath my arm and wrenching free. The rapidity and skill of her movement so surprised me that I was caught off-guard when she twisted about and struck a stunning blow across the side of my neck, knocking me headfirst into a large bookcase, whereupon a shelf collapsed. Books tumbled about me and I gasped in pain, but there was precious little air in that gasp and my head swam.

“Get out, I am warning you!” she whispered, then sank against the wall.

With no time to ponder where she might have learned such a trick, I leaped at her again and secured a firm grip of her collar and sleeve, employing the jujitsu “waltz” to swing her again towards the door. She attempted to trip me; by reflex, I countered the trip with a hip throw. We crashed to the carpet, sending fragments of paper fluttering up around us like gypsy moths, and rolled, each of us struggling for the dominant position. Alta Marhevka was far stronger than she looked. My heart pounding like a trip-hammer, my lips and fingertips tingling, I could not help but snatch another gasp, which set me choking.

As we fought I was desperately aware that no ordinary jiujitsu lock would avail, for if I simply held Alta helpless then the gas would surely overcome us both.

Fortunately, she was weakening even faster than I. As we rolled against the wall I became able, with considerable effort, to brace against it and so regain my stance, half-dragging the girl up with me. Grasping her left wrist in my right hand, I entwined my left arm over and under hers, achieving the elbow lock that Mr. Barton-Wright advises for removing troublesome persons. Via this leverage advantage I propelled her across the room and through the open door, and not an instant too soon, for my head was pounding and purple spots flared and popped before my eyes like Hong Kong fireworks.

I hustled her down the hall until I could not possibly hold my breath any longer and then released her, drawing in a great, whooping gulp of fresh air and then falling back against a neighbouring door, stricken with another coughing fit. Alta staggered and fell to her hands and knees, likewise coughing and almost insensible. Though I could scarcely make one thought follow another, I tried to be alert to any attempt on her part to rally, for if she made it past me and back into that death-room again, all would be lost.

Just then the sound of heavy boots issued from the stairwell, and a door burst open to reveal two New York constables. I’ve had decidedly mixed experiences with their London counterparts in recent times, but I confess that I was very glad to see these two fellows.

“Which of you is Alta Marhevka?” demanded the taller of the pair, a lanky chap with gimlets for eyes.

Gaze downcast, frighteningly pale of complexion and completely exhausted, she tremblingly raised her right hand, at which, to my astonishment, they dragged her up from the floor and clapped her in handcuffs!

The shorter constable, or “officer” I should say, was built like a wrestler or prizefighter, with a ruddy complexion and a down-turned mouth beneath bristling moustaches. “Miss Marhevka,” he began, “you are hereby placed under arrest on suspicion of having murdered Doctor William Latson. Have you anything to say for yourself?”

Alta simply muttered something that sounded like “my gourah”, over and over again, “my gourah”, as they bundled her through the stairwell door and down the stairs. Scarcely believing my eyes, I tried to call after them –

“Wait! Wait, that girl has just tried to commit suicide by gas!”

– but my voice was so weakened by coughing that I could not hope to make them hear me, and they were gone before I could gather the strength to follow.

![]()

By about mid-day, assisted by the concerned ministrations of our hostess, Mrs. Washington, I had sufficiently recovered my wits and equilibrium to be able to help attend to Miss Marhevka’s room. I had explained the morning’s events and both Mrs. Washington and her husband were quite taken aback by it all. After Mr. Washington had turned off the gas and opened all the windows, the room soon seemed ordinary once again, save for the three broken lamps, the collapsed bookshelf and the scraps of notepaper strewn about the floor.

“In all my days I’ve never seen such a thing,” he remarked as he picked up a ragged piece of notepaper. “Listen to this; ‘Even if I have not succeeded, at least I have known life to the utmost’. What’s that all about?”

“‘If you want to be good, be dead – you cannot be good without'”, read Mrs. Washington from another scrap. “For Heaven’s sake, what was the poor girl thinking?”

Indeed, upon every scrap of paper was written, in a careful, educated hand, some snatch of poetry or odd aphorism:

“A woman should be like a flame – dainty, exquisite and fine, high and strong – strong – strong.”

“As you think, so you become.”

“The sinful painter drapes his goddess because she is still naked, being dust. The godlike painter will not so deform.”

And, repeated over and over again, on many papers in both ink and pencil, one phrase:

“Forth speed the strong to the pulse of the day.”

Here, indeed, was a mystery worthy of my mettle! After we had gathered the scraps and replaced the books upon the shelf, Mr. Washington set about replacing the lamps. I then asked them for their impressions of Alta Marhevka.

“Oh, she’s a very clever girl,” said Mrs. Washington. “See all these books? I’m sure she’s read every one, and could quote you chapter and verse.”

“Do you know where she worked?”

“Yes, she was secretary to a medical man on Riverside Drive,” she replied. “I think it was that Dr. Latson that you mentioned, the man who was murdered – oh, it’s so awful!”

She became teary and so I lent her my handkerchief. That Miss Marhevka was a devotee of the New Thought movement, or perhaps some branch of Theosophy, was quite apparent, going by her library. Titles included The Secrets of Mental Supremacy, The Enlightened Life, The Attainment of Efficiency, A Catechism of Health and dozens more in a similar vein, each and every one of them written or edited by Dr. William R.C. Latson. Was he the “gourah” whose name she had invoked as she was being dragged away in irons? I knew that gourah, or guru, was a Hindoo term, meaning a teacher of spirituality; I associated it with the occult practice of yoga.

Mysteries upon mysteries … but at that moment, the same two constables who had hustled Miss Marhevka away appeared in the doorway.

“You!” the shorter one began, glaring and pointing at me most rudely. “Why did you not tell us that the other girl had tried to do herself in?”

“Well, I would have done, had you given me a chance!” I snapped back. “I was weakened by the gas fumes – surely you must have smelled it when you entered the hall?”

He eyed me suspiciously, then turned and whispered to his colleague. Although I could not hear him, I could easily read his lips – “Say, Frank, she must be one of these ‘bee girls’.”

At this, the taller officer – Frank, apparently – nodded and whispered back, “See what she knows, Eddie.” Then, politely but firmly, he ushered Mr. and Mrs. Washington out of the room.

“Look here, Miss, you may as well come clean,” the shorter constable said, as Frank closed the door behind the Washingtons and began to gather up the scraps of notepaper.

“Just be honest and save us all some time and trouble, there’s a good girl.”

In such situations, I have always found it best to speak forthrightly, for men often expect women to be timorous and flustered and many will exploit those responses if it serves their own interests. I introduced myself, sustaining candid eye contact with each of them in turn, and then calmly and truthfully explained my circumstances. I gave them partial credit for not interrupting.

“So you claim you had no acquaintance of Alta Marhevka or Dr. William Latson prior to your arrival here?”, Officer Eddie demanded when I was done. “No correspondence? Nothing at all?”

I gazed at him evenly.

“I was Alta’s neighbour for two days and that is the extent of our association,” I replied. “I have no other knowledge of this Latson.”

They exchanged a glance and I sensed that they believed me.

“Now,” I pressed, “what is going on here?”

“Well, never you mind about that,” Officer Frank replied firmly, as he stuffed Alta’s notes into a large brown folder. “If what you say is true, then the less you know about that business, the better for you.”

They turned as if to leave, but I spoke sharply:

“Will you at least tell me – is the poor girl recovered from her ordeal?”

“She’s in a bad way, Miss Lee,” Eddie replied. “In Washington Heights hospital and under guard, and she’ll go straight to Bellevue … if she lives.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Bellevue – that’s the nut-house, Miss.”

![]()

My lecture that evening was well-received, though I confess that I was distracted throughout by the puzzling events into which I had been thrown. Afterwards, I excused myself as soon as I could from the academic chat and set out for Greenwich Village alone.

En route, I purchased a number of newspapers; as I had surmised, they were full of the story of my erstwhile neighbour and the mysterious death of her former employer, which had evidently occurred the previous day. I returned to the White Horse tavern, sat down in a booth with a stiff brandy and tried to make sense of it all.

Apparently, a young eyewitness – the son of Dr. Latson’s landlord – had observed Miss Marhevka climbing out of the window of the doctor’s apartment on Riverside Drive, before she fled the scene in what seemed to be a confused and agitated state. Alarmed, the boy had alerted his father, who, unable to contact Dr. Latson either by telephone or by knocking at his door, had let himself in – only to discover his tenant’s body, dead of a gunshot wound up under the right side of his jaw and kneeling before the couch in his clinic.

The police were called and found a pistol beneath the dead man’s body, along with a note in his handwriting, which read, rather cryptically: “Gertie and Mother, I have done my best – death.”

Investigation at the scene had revealed half-empty vials of morphine and also hyoscine, which I understood to be a particularly nasty hallucinogen, often associated with cases of poisoning. This, despite Dr. Latson’s reputation as a clean-living man – indeed, as a staunch advocate of temperance and self-improvement, via his many books and articles.

The papers also revealed that Dr. Latson had been in financial difficulties and had, just the day before his death, been served with a “summons of dispossess proceedings” – effectively, an eviction notice.

On the face of it, everything seemed to point towards a tragic suicide, aside from the bizarre behaviour of Miss Alta Marhevka. The newspapermen could not agree on the spelling of her surname, rendering it as “Marhezka”, “Merhelka” and yet other variants, but most took a lurid delight in speculating as to the nature of her relationship with the deceased doctor. The reporters had obviously seen at least some of her would-be death notes, for several were quoted verbatim, and much remarked upon – “Weird with awful possibilities of a strange Oriental code”, indeed!

These reports offered no clues, however, as to what the police officer might have meant by accusing me of being “one of these bee girls”.

Having several free days before my return voyage on the Olympic, and the feeling that there was even more to the Latson/Marhevka affair than met the eye, I begged off my colleagues’ offers of sightseeing tours and set about investigating the mystery.

As much as the newspapermen were making of the “god-man scandal”, it seemed evident to me that some intersection of prosaic reality and “mystical psychology” might well provide the key to this strange case. Despite his outward-seeming success as an author and medical practitioner, Latson had been in dire financial straits and was about to lose his home. His reason had been clouded by drink and drugs. Under such pressures, what might motivate a man whose every waking hour seemed to have been devoted to his strange philosophies?

I had an inkling that his storied penthouse might yield a clue or three.

![]()

LATSON’S AFFINITY HELD IN HOSPITAL TO FOIL SUICIDE

Girl Complains Because She Isn’t Permitted to Die.

Letters Found.

NEW YORK, May 14.—By order of Coroner Feinberg. Alta Marhevka, the beautiful young student of occultism who tried to commit suicide following the death of Dr. William R. Latson, the eclectic theosophist, with whom she was in love, was kept the Washington Heights Hospital today instead of being arraigned in the Harlem court on the charge of trying to do away with herself.

The coroner believes the girl will again try to kill herself if she is discharged by the court while possessed of the mania that Latson was a Man-God whose spirit she must join. She will therefore not be arraigned until after the inquest, when the coroner believes she will be more normal.

Early today the girl’s father said he would take her back, although he had disowned her.

The girl today persisted in the same attitude toward life and death that she has displayed all throughout. Her one anxiety seems to be how to break the thread which binds her to earth In order to join in the mysterious beyond her dead “Gourah.” When told that her adherence to this determination to join the student of Oriental mysticism would probably result in her permanent incarceration in the asylum she became feverishly uneasy.

“What can I do?” she cried. “As long as I stay here my whole being Is fettered. All I ask is death. How I join my master? I do not care, so long as I can meet him where he is waiting for me. I pray heaven I may get another chance tonight to join Dr. Latson, for I know that once we are together again he will love me with his whole soul.” All through the night the girl tossed on her bed in the hospital, safely held in padded restraints, recovering from the effects of the gas she had taken yesterday morning in an effort to kill herself.

That the girl in the case fully thought out her action was evidenced by scraps of writing found in her room. The policeman who first entered the room found this sheet there:

“Remorse—Darling: Love is so sweet. We took It too lightly: gazed on it too brightly: sensed it too deep. It was the great god flew – dear, the fault was not in you, but I – who, wayward – urged you on to this.”

As luck would have it, the evening was stormy. Dead leaves and paper rubbish swirled and scudded forebodingly about the streets as I made my way by Taxi cab to the late Dr. Latson’s surgery and apartment on Riverside Drive. The surgery door was clearly marked with a small brass plaque announcing Dr. Latson’s name and business hours, but I could not locate a separate door for his apartment.

The surgery door was now locked, of course, and a notice pasted to it prohibited any disturbance, by orders of the New York City police department. Still, it was a simple lock, and I am adept with hairpins. I checked in both directions, up and down the street, then tucked my ball-handled Sanderson special under my arm and set to work; in a few moments the door swung open and I stepped inside.

The light of my electric lantern swept the walls, revealing nothing but a nicely-appointed vestibule, typical of any moderately prosperous doctor’s office apart from its vaguely Oriental ambiance. There was a neat reception area, including the desk where, presumably, Miss Marhevka had fulfilled the duties of her office; a fine-looking rug of possibly Egyptian origin and a small suite of comfortable-looking chairs, all polished leather and brass studs.

I tipped the lantern upwards – risking the slight chance that a passer-by, braving the downpour, might spot its beam through the windows – and saw that a large, fantastically decorated lantern of paper and bamboo hung from the ceiling – a Korean ornament, unless I was much mistaken.

I was surprised to find that the next room, which had obviously served as Dr. Latson’s clinic, was scarcely larger than the vestibule – an intimate chamber, indeed, and presumably the site of the doctor’s death.

I had gathered from the newspaper reports that his professional specialties had shifted over the years, from naturopathy to dermatology and most recently to psychiatry. Three windowless walls were draped with rich, dark green and burgundy fabrics, while the fourth was a bookcase from floor to ceiling. The only furniture was an ottoman couch, a small side-table bearing a stained glass lamp and a large armchair, whose darkly colourful embroidery style I recognised as Tibetan.

Evidently, whatever the precise nature of the ministrations the doctor had provided in this close room, they had been of a primarily psychological nature.

Shining my lantern upon the ottoman I saw an ominous dark stain that confirmed my previous intuition; this was where the fatal bullet had been fired. Otherwise, the room seemed free of any clues … but I have never been easily dissuaded.

Clearly, there must be more to the apartment than the vestibule and this odd chamber, for this had been Latson’s home as well as his clinic and office. Therefore, logic suggested, there must be a hidden exit. Crossing to the bookshelf, I commenced the requisite proddings, tuggings and twistings and was soon rewarded by a soft click. I pressed forward and the heavy shelves swung smoothly back, revealing a short corridor leading into the doctor’s well-appointed, but quite ordinary living room. As I entered I noted only one somewhat unusual feature – a spiral staircase leading up through a circular gap in the ceiling.

As I approached the staircase, though, I perceived the sound of music, very faint but almost familiar, and the closer I went, the more familiar it became. By the time I had a hand on the railing, I knew the music for what it was. At the summit of this strange vertical tunnel, somewhere up above me in this staid Riverside Drive apartment building, was being played the haunting gamelan music of exotic Java, and if that was not somehow connected to the mystery of Miss Marhevka’s “god-man”, then I would eat my hat with molasses.

![]()

The hypnotically rhythmic chiming and drumming increased in volume as I crept cat-footed up the winding steps. I judged that I had climbed some four stories up that dim spiral before reaching the top floor, whereupon I was faced with a billowy hanging fabric, gauzy in texture and honey-gold in hue, that completely obscured whatever might be seen in the room beyond. Fortunately, the room was brightly lit, so the fabric also served to conceal me from whomever might be in there.

Very cautiously, I pressed my eye to the hanging gauze and, beyond, I beheld an extraordinary scene. The chamber was decorated as was the downstairs clinic, its walls entirely covered in heavy green and burgundy draperies. At the far end, directly opposite my hiding place, was a great, unoccupied throne upon a dais, both immaculately carved of some dark wood in the Javanese fashion, with gold highlights. The throne was surmounted by hangings of red velvet topped with a bulbous, conical wickerwork structure that I recognized as a skep – an artificial beehive.

Against the western wall was a broad lower dais, upon which sat three young women; barefoot, corsetless and dressed in simple white shifts, playing the gongs and metallophones of gamelan tradition. As they played, a group of five more women, similarly dressed and unshod, danced upon the polished floorboards before the throne. The dancers’ shifts were girded at the waists with cords, whose tassels swung as they stepped and spun, and each of them bore a shining keris, a long dagger with a wavy blade.

Their dancing was marvelously skilled, combining precise gestural symbolism with the athletic grace of ballet, punctuated by grotesque postures recalling the mythology of Rangda, the cannibal “Witch Queen” of the Indonesian islands. In all, it was evocative of the ceremonial dancing I had seen in Balinese villages during my girlhood travels with my parents; yet it was not exactly that. For one thing, in Indonesia, only men were permitted to dance with the keris.

Suddenly, just as the music reached a crescendo, the three musicians stopped playing, and the only sound in the room was the deep, long, reverberating note of a large gong. At that instant, the dancers all froze in mid-movement, with scarcely a tremble to betray the effort of holding their strenuous poses, and then, as one, they turned their keris daggers upon themselves! I came very close to crying out in alarm, but their movement was so swift that it was accomplished before I had the chance to draw breath.

Each woman’s face was a mask of fierce concentration as she bore the lethal point of her weapon against her chest, seemingly with all the strength of both arms; and yet the deadly blades did not pierce them. Not a one screamed in pain, and I saw no blood. It was as if the daggers could not penetrate their skin.

Then the music started again, and they re-entered their dance. Still, no-one fainted, nor did blood flow. During my months of training with Persephone and her Amazons in Mr. Barton-Wright’s London gymnasium, I had grown accustomed to seeing young women execute feats of great calisthenic daring and antagonistic skill, but I had never seen anything like that.

So entranced was I, in fact, that I entirely failed to notice that I was no longer alone in my hiding spot behind the gauzy curtain until I felt myself shoved bodily from behind. I staggered forward violently, my hands coming up to guard my face and ensnarling themselves in the gauze, which tore free and wafted down to envelop my upper body.

“Interloper! Intruder!”

The music stopped again and the dancers leapt away in startled confusion as I plunged into their midst, wrenching around to face whoever had pushed me while trying to disengage from the entangling gauze.

I found myself facing a furious woman, her blond hair streaming back as she rushed at me, her hands outstretched as claws. Reflexively I met her charge with the jiujitsu “stomach throw”, simultaneously falling back and leveraging one foot into her abdomen. The momentum of her attack propelled her over my head in a dangerous somersault, but she responded skilfully, rolling with the fall rather than crashing. I scrambled back to my feet, pulling free of the curtain fabric and raising my umbrella in what my cohort and instructress Miss Sanderson was pleased to call the “rear guard”, my left hand outstretched before me.

The blond woman raised her own hands in a defensive posture that I did not recognise, but which bespoke training in the antagonistic arts. I quickly assessed my situation. The erstwhile dancers had somewhat recovered their collective composure and were now circled about me, all seeming poised to attack if need be. Their musician companions had left their dais and added to their number. I was not here to fight and could not hope to defeat nine women, in any case; discretion would be the better part of valor.

“Wait!” I called out, raising my stance and lowering my arms. “There is no need for further violence!”

“Take her, sisters!” cried the blond woman, and I did not resist as they seized me, confiscated my umbrella and bound my wrists tightly behind my back with one of the tasseled cords. I was then forced to my knees before the woman who had attacked me from behind. She glared at me.

“Who are you and why are you here?” she demanded.

It did not take terribly long for me to explain myself, including details that proved my first-hand acquaintance with Alta Marhevka and the events of her attempted suicide – details that I could not have guessed at, nor gleaned from that day’s newspapers. As I explained my role in her rescue, the heated atmosphere in that strange room evened considerably, and the women began to glance at each other uncertainly, now seeming less like vengeful witch-queens and more like the gaggle of New York society girls that they undoubtedly were in daily life; though I could not account for their feat with the daggers.

I concluded by apologizing for interrupting their ritual and my blond interrogator seemed satisfied with my story.

“Release her,” she commanded imperiously, and so I found myself gratefully free and rubbing some feeling back into my numbed hands.

“I’m sorry for attacking you, Miss Lee,” she said, “but we have occasionally had to deal with hostile outsiders in the past, and I took you for a lurking spy or even assassin.” Her accent was not quite American – some Swedish, perhaps? – and her manner was somehow both slightly debauched and haughty. She seemed only a few years older than I.

“My name is Alma Hirsig,” she continued, “and, in Alta’s absence, I have assumed the role of Queen Bee. I know that you must have many questions and I may be able to answer some of them, but our immediate concern is for Alta’s well-being. That was the purpose of our rite this evening, to shore up resolve and lend her strength on the astral plane.”

(If I may be permitted an aside here, I have never had much truck with spiritualism. Indeed, I have occasionally been invited to delve into the doings of professional spiritualists. Every man jack of them has been either a cynical fraud, using legerdemain to prey upon their clients’ vulnerabilities and superstitions, or a sincere but deluded crank who has somehow become convinced of their own powers to communicate with the dearly departed.)

“Alma,” ventured one of the girls – a petite and wide-eyed brunette – “do you suppose it worked? We didn’t quite finish.”

“Even assuming that it did, Alta is in a precarious state of being,” Miss Hirsig replied. “At worst, she will find a way to use all that borrowed strength towards her final purpose.”

Some of the women gasped at this, and others shook their heads sorrowfully.

“I take it that you believe she still intends suicide?”, I asked.

“Undoubtedly so,” said Alma Hirsig. “Any one of us might do the same, were we in her position.”

With an elaborate bow and wave of the hand, she dismissed the now-grieving dancers and musicians, who offered a graceful, ritualistic bow in return, and all intoned a phrase that I recalled from one of Miss Marhevka’s notes – “Forth speed the strong”. They then obediently filed out through the doorway leading to the spiral staircase.

Miss Hirsig invited me to sit at a low table surrounded with colorful cushions, glanced towards the door and, seemingly satisfied that we were not to be disturbed, began to speak in low, urgent tones.

“As you must have gathered, Miss Lee, we are a select and secretive group. I won’t attempt to explain the details of our theology – they never make sense to outsiders anyway – so it will suffice to say that Dr. Latson was a genius, but that he was also very human. We – well, he and Alta, really – have been compiling a new religion, as it were, for this new century, drawing in all that is best from modern American soul-science and from the ancient traditions of the Orient.”

Privately, I marked Latson down as a spiritualistic Edward Barton-Wright; each man an eclecticist and iconoclast, making his mark via an experimental union of Asian and European elements. The main difference being that Mr. Barton-Wright was an eminently practical fellow. Neither as a fighter, nor as a healer, had he any time for mystical foofaraw; in fact, he had written an expose of certain tricks of leverage that were commonly passed off as evidence of superhuman strength by charlatans in the music halls. Dr. Latson, by way of contrast, had clearly tread a more occult path.

Miss Hirsig looked at me appraisingly and then inquired, “Do you mind if I ask after your ancestry?”

“My father is Chinese and my mother is English,” I replied.

“Ah, Chinese – so that explains your jiujitsu,” she observed knowingly, with the air of someone who rather delights in the dropping of names and hinting at occult knowledge.

“Actually, no – I’ve learned some self-defense recently, but that has been through the agency of friends in London,” I clarified. “My father is a businessman and a pacifist.”

I did not trouble to add further that, as jiujitsu is a Japanese art, my father was rather doubly unlikely to have been my teacher in this area. In fact, the closest he had ever come to antagonistics was to have hired some shway jao wrestlers as bodyguards during our time in Hong Kong.

Something passed behind Miss Hirsig’s eyes, but I could not tell what it was, and she shook it off forthwith.

“Well, in any case, you’re clearly a woman of action and of some shrewdness,” she continued, “to have come this far in your investigation. Also, of course, we should be grateful to you for saving young Alta’s life. Have you any knowledge of her present state?”

“The officer who arrested her mentioned that she was taken to Washington Heights Hospital,” I replied. “He thought she’d be taken to Bellvue, if she survived.”

Miss Hirsig sighed and briefly closed her eyes.

“I’ve been at the the station all day,” she confided, “and, as far as I could make out from the babbling of journalists and patrolmen, Alta regained consciousness this afternoon. She’s probably locked up in Bellvue as we speak. Damn it, we must get to her before she recovers enough to finish herself off!”

“She’ll surely be kept restrained and under close watch,” I offered.

“No doubt, and that makes our cause all the more urgent,” Miss Hirsig replied. “Alta has many gifts, but she is beset by a horror for any form of confinement. To be strapped to a hospital bed and observed night and day … that will be torture enough to drive her mad, if she is not there already. She is something of a genius herself and if she can’t out-wit a suicide watchman, I’d be much surprised. For that matter, she’s well-trained in Dr. Latson’s method of self defense, so even if she can’t out-wit her guard, she can probably out-match him.”

I well recalled Miss Marhevka’s startling speed and skill in antagonistics.

“She must have loved the doctor very much,” I observed.

“Oh, yes, Miss Lee. They have been lovers for a long time – longer than has been at all healthy for Alta, if you want my candid opinion. It’s all so very complicated … but, as I’ve said, Dr. Latson was very human.”

Alma Hirsig sighed again and seemed to be waiting for me to prompt her. I found her theatrical affectations irritating, but young Alta was clearly in danger, so I obliged by asking, “Do you doubt that he killed himself?”

“No, not at all. His medical practice was failing and he was about to be evicted. What the police have said about finding morphine and hyoscine – well, I never actually saw him partake of drugs, but I wouldn’t be surprised. He put up a very good front – good enough to fool the other Hive girls – but I’ve seen the signs before, in other men.”

Miss Hirsig leant forward.

“What most troubles me right now, though, is the fact that Dr. Latson was shot under his right jaw!”

She paused as if to let me draw my own conclusions, but I impatiently shook my head, having no way of knowing what she was driving at.

“The doctor had suffered a break of his right arm while playing football in college, and it healed badly” she continued. “He could barely bend that arm at all, certainly not far enough to bring a pistol into that position!” She mimed the action for dramatic effect. “It is simply impossible for him to have done so.”

“Then I don’t take your meaning,” I replied. “If he could not have fired the fatal shot …”

“Our, well, ‘religion’, if that is how one wishes to think of it, makes much of certain secret powers of the mind and body,” said Miss Hirsig. “As you saw earlier, it is possible to enter such a trance as to be impervious to sharp knives. The doctor and Alta did much private experimentation in that sphere, delving deeply into hypnotism and altered states of consciousness.

In sum, Miss Lee, yes, I very much believe that Dr. Latson killed himself – but I think that Alta Marhevka was his weapon!”

Alma Hirsig, evidently being much given to hinting at the ineffable – or simply the distasteful – then paused for dramatic effect, her eyes wide open.

As far as I knew, no entranced subject could be compelled to carry out an action that was truly against their best judgment. But perhaps a young girl, in thrall to a charismatic older man – her God-Man – could be so compelled. Perhaps especially if he was desperate … if he begged her … might such a woman be mesmerically induced to kill out of mercy?

Miss Hirsig went on to explain that Alta was utterly devoted to Latson’s strange creed, which held that death was simply the stepping stone to a kind of etheric, blissful state of being she called Samadhi. Finding herself bereft, Alta would have no qualms about joining him in that state. The police, meanwhile, would be interrogating her, sifting the evidence, and might well conclude that she had committed murder out of some womanish spite, then attempted to take her own life in remorse, or to escape the misery of life-long imprisonment.

In any case, it was clear that Alta Marhevka was living her personal version of Hell, and that her future looked grim indeed.

“We must get to her, and very soon, Miss Lee,” Alma concluded. “Alta trusts us as sisters and we will be able to persuade her that life is still worth living. If all else fails, she is susceptible to certain mantras …” she trailed off and glanced at me, and I intuited that she had spoken out of turn, forgetting my status as an outsider to their cult.

“The trouble is,” Miss Hirsig continued, “we can’t reach her. The other girls are looking to me for leadership, being the eldest and, shall we say, the most experienced in the ways of the world, but I confess that I have no idea how to get past the guards at Bellvue.” She gazed at me for a moment, then looked down, her shoulders slumped, and shook her head sadly.

“We were once rivals, Alta and I,” she confessed, “but this … I can’t bear the thought …”

“Miss Hirsig,” I began, “I think that I may be able to help you.”

BELLVUE INVADED BY “BEE GIRLS”

NEW YORK, MAY 15. – Bellvue Hospital was today the scene of much confusion as police and hospital warders found themselves beset by a gaggle of young ladies, curiously described by Officer Eddie O’Brien, who was on the scene, as “Bee Girls”.

The invasion, for so it has been styled, began shortly after mid-day, when at least twelve girls, all identically dressed in some form of Oriental robes, entered the main foyer from First Avenue. Several made their way forthrightly to the reception desk and began peppering the receptionist with nonsensical questions. Others of their number were observed to gather near the security door.

When the door was opened from the other side, all the girls swarmed forth and ran through it, thereafter racing every which way through the corridors and up and down stairs, causing some alarm as to their purpose. As soon as one or two were rounded up by orderlies, still others would sally forth.

It took some forty minutes until they were all accounted for, whereupon it was explained that they were engaged in a sorority prank. After a stern talking-to and threats of trespass charges should they return, they were released to go about their silly way.

Officer O’Brien would not offer further comment upon his “Bee Girl” remark, except to say that: “I don’t think they’ve done any real harm today. They might even have done some good.”

MYSTIC SPELL PASSES FROM ALTA MARHEVKA

Girl Awakens to Find Hypnotic Spell of Dead Doctor Gone and Love for Life Returns.

NEW YORK, May 16. – A pallid-faced young girl opened her eyes to-day in a room flooded with sunlight. She blinked in apparent wonder at the bulky brass buttoned guardian at the bedside. “Why,’ she sighed perplexedly. “I feel so – so different. I – I have passed through a frightful nightmare.” Alta Marhevka, who, for slx years, followed blindly the paths of Hindoo lore blazed by her “Gourah” – the slain Dr. W. R.C. Latson – had found her-self.

Alta Marhevka, mystical young seeress, was gone. and in her place on the hospital pallet lay Ida Rosenthal, simple young Ghetto maiden. It as a transformation sudden and startling to the authorities of the Bellevue Hospital, where the young girl is under arrest on a charge of attempted suicide following the unexplained violent death of Dr. Latson.

“I have made a great mistake. I shall never again try to destroy my-self,” shuddered the girl. “Socrates quaffed the hemlock,” she half laughed to one of the nurses, “but I shall quaff the sweet wine of youth.” The girl pupil said to-day that she had no recollection of the events of the past four days. Whether the man, now dead, fired the shot that cut short his life, or whether the slender hand of the girl, guided by the masterful spirit of her “man-god,” pulled the trigger, will perhaps never be known.

But one positive fact remains that should be of interest to medico-psychologists – the girl’s eye action to-day was that of a person who has shaken off the enthralling power of a more potent personality, or who has recovered from the effects of a powerful drug. “Dead or alive, you will always be mine,” were the doctor’s last words to her. But now that his living presence has been removed, the girl is free. Her “Gourah” could experiment upon her brilliant intellect yesterday, but to-day her life is her own – to live it as she herself directs.

A few words will suffice to describe what remains of this odd adventure. Having successfully employed a tactic much-used by my Amazon friends in smuggling fugitive suffragettes to and from various secure locations, I felt that I had done what I could to assist Alma, Alta – or Ida, as it seemed – and the “Bee Girls”. In any case, I had the next morning to depart again for England, and so passed a distracted week aboard the R.M.S. Olympic, pleased that Alta/Ida seemed to have returned to herself again but unknowing as to her fate at the hands of the law.

Upon our berth at Southampton I immediately checked The Times for any news. I was surprised to discover that the coroners had been unable to agree on the circumstances of Latson’s death – one insisted that it must have been suicide, while his colleague insisted the opposite.

The judge, nevertheless, found that Ida Rosenthal would not be held on suspicion of Dr. Latson’s murder. A few days later, the court gave a final verdict of “death by suicide”, and so ended the mysterious case of the God-Man of Riverside Drive; though, like the Bellvue doctors, I found myself startled by the sudden transformation from Alta Marhevka back to Ida Rosenthal. I could not help but wonder if, perhaps, she was not the greater mystery.

I still wondered, also, about the Bee Girls’ feat with their keris daggers, and the next time I took exercise at Mr. Barton-Wright’s Bartitsu Club, I asked if he could explain it. Smiling (a little grimly, I thought), he retired momentarily to his office, and then emerged bearing a wickedly sharp-looking bayonet. Placing it against his chest, he assumed the same posture as had the Bee Girls and, just as they had, appeared to bear mightily upon the blade, but of course it did him no harm.

“The trick, Miss Lee, is largely of the mind,” he explained. “An entranced dancer is typically in a highly suggestible state and they can easily believe that they really are trying to stab themselves. Though it looks and feels dangerous, in fact they are simply tensing all their muscles against each other. It is almost a self-induced paralysis.”

He pondered the bayonet for a moment and then, spinning on his heel, sent it flashing through the air and directly into the thick dart-board Mr. Uyenishi used for shuriken practice. It stuck into the target with a fearsome thunk and vibrated for a moment. Mr. Barton-Wright then turned back to me and noted somberly, “Of course, the Boxer rebels of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist Society in China believed that they were invulnerable to attack by blade, gunshot and cannon-fire. Their belief made them courageous, but so many died …”

Some weeks later I was encouraged to receive a letter from Ida, who apologised profusely for having fought me in her apartment – “I was quite out of my mind with grief and religious fervour”, she noted – and thanked me for helping her friends to reach her. She also mentioned that she intended to go sub rosa for some time, having had more than her fill of occult scandals and newspaper-men.

POST-SCRIPT

I have just this morning received a telegram from Ida Rosenthal, which reads:

MISS LEE. EN ROUTE TO LONDON. SEEK DETECTIVE TRAINING FROM THE BEST RE NEW POSITION WITH MAGICIAN H.HOUDINI. FORTH SPEED THE STRONG. REGARDS IDA R.

How very intriguing …