From Interviews

Neal Stephenson foreshadows “Suffrajitsu”

An excerpt from an interview by Douglas Wolk for the io9 website on May 30, 2012:

I ask Stephenson about the cane-fighting subgroup that drew Greg and Erik Bear into the project, and he’s off into explanatory mode again. (I’m not complaining. I could listen to Neal Stephenson explain stuff all day.) “It’s an interesting thing,” Stephenson says, “because from a distance 19th-century martial arts looks kind of dorky — it looks like Monty Python. It ties into everything we believe about the Victorians: that they were out of touch with their bodies, that they didn’t really understand medicine very well, and that they were uncomfortable with physical activities. But once you get into it, you find that these people really knew what they were doing in terms of physical culture, in terms of self-defense. Victorians were really serious about staying fit.

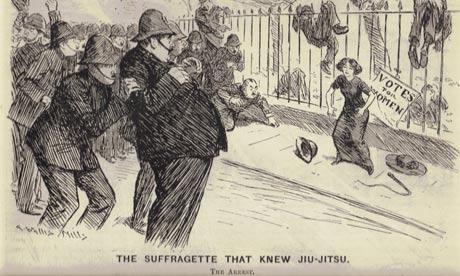

Part of what makes this an interesting story is how, in the 19th century, jiujitsu was adopted by women. This guy Barton-Wright brought jiujitsu to London. He came back from Japan and created a club called the Bartitsu Club. He taught the mixed martial art of jiujitsu, bare-knuckle fighting, savate, stick fighting and a few other things. He brought in a couple of teachers from Japan, and would take them around the music halls—have them challenge huge, burly guys and throw them around. This had an unintentional side effect that suffragettes would see these performances, and decide they wanted to learn self-defense: ‘I want to defeat a man!’ Jiujitsu as a ‘husband-tamer’!

We want to do a side-story quest thing about the jiujitsu suffragettes. The image that we’re all dying to get into a full-page spread in a comic book is this lineup of Edwardian women with the flowered hats and the long skirts and the bustles, and they’re all walking eight abreast down a London street, swaggering toward the camera and approaching a bunch of bobbies… if we could get that image in some medium, that would be a good thing.”

“Edith Garrud: a public vote for the suffragette who taught martial arts” (2012)

Click here to read journalist Rachel Williams’ article for The Guardian on Suffragette jiujitsu trainer Edith Garrud, including quotes from Tony Wolf.

“Suffrajitsu” and the Foreworld Saga

In this interview featured on Amazon.com’s Kindle Daily Post blog, Foreworld author Mark Teppo drops a hint on the cryptic connection between Arthurian myth and Miss Persephone Wright, the protagonist of Suffrajitsu:

In our initial presentation of the Foreworld Saga, our focus has been on the heretofore neglected martial arts of the West. We have sought to bring to life the rich and varied fighting arts that are now being rediscovered and enthusiastically explored by numerous study groups around the world. But our underlying foundation of Foreworld has always been a crypto-pagan mythic structure. One that Percival glimpsed a portion of during his experience in the woods; one that lay underneath the life and death of Genghis Khan. And now, with Katabasis and Siege Perilous, the remaining two volumes of the Mongoliad Cycle, the mystery of the sprig and the cup come to the forefront. It all hinges on the knight for all seasons—the singular one born of every generation: Percival, the knight of the Grail.

It doesn’t end here, either. Next year, Suffrajitsu, a graphic serial written by Tony Wolf and drawn by João Vieira, will be released. It takes place in Victorian England and stars Mr. Bartitsu himself, Edward Barton-Wright, and his liberated niece Persephone Wright — “Persi” as she is known to her friends …

An interview with Emelyne Godfrey on women’s self-defence during the “long 19th century”

Emelyne Godfrey is the author of Masculinity, Crime and Self-Defence in Victorian Literature and its sister volume, Femininity, Crime and Self-Defence in Victorian Literature and Society.

Q – Emy, can you describe how the new book fits in to your ongoing research on the topic of self defence during the “long Victorian era”?

A – It was effectively the third chapter of my PhD on Victorians and self-defence (which focused on H. G. Wells’ Ann Veronica and women’s self-defence and martial arts in Edwardian literature) but as I started researching for this book, I found so much new material so it felt as if I was starting the research from scratch. Writing it took somewhat longer than expected!

Q – What were your motivations for writing on this topic? In particular, how did the new book come about?

A – The books were ultimately the result of my mother’s suggestion a number of years ago that I go on a self-defence course which she had seen advertised on TV. At the time, I was a student at Birkbeck College, London, doing the MA in Victorian Studies and was casting about in my mind for a topic for a PhD and was reading about the Ripper murders when it occurred to me to ask how men and women defended themselves during this time. Alongside that, I learned from speaking to women after the self-defence course was that concepts of safety as they relate to feminism were so subjective.

Q – In what way?

A – Our self-defence instructor told us she refused to go out on her own after 8pm, which some women said didn’t sound very empowering, or feasible, especially if you were a student at Birkbeck, when some classes ended at 9pm. What was empowering? Avoiding danger or staying out a bit later and taking the last bus home? Other questions also popped up: how did one respond to being accosted or threatened, where were the sources of danger, and did men and women assess threat in different ways. I started interviewing anybody I saw about the subject of safety and I was passionate about seeking the answers. Intriguingly, men and women were debating these questions in the Victorian era, a time which saw a massive growth in London’s population and also witnessed the growing numbers of independent women of all backgrounds engaged in all kinds of work, and also philanthropy, travel and political campaigning.

Q – The subtitle refers to “Dagger-Fans and Suffragettes” – can you tell us what a “Dagger-Fan” is?

A – The dagger-fan was a novelty hand fan, designed in the shape of a dagger in its sheath. It’s kept at The Fan Museum in Greenwich, which displays some gorgeous fans from throughout the ages. At least one contemporary commentator observed with humour that such a dangerously shaped accessory might subtly discourage unwanted admirers who might lurk on trains or at street corner.

The dagger-fan is symbolic of all the many kinds of subtle means, discussed in this book, that a woman could employ to deflect threat while out and about – gesturing with her fan, a humorous retort, disguise, a clever use of eye contact. As Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Mona Caird’s The Wing of Azrael, remind us, the ‘marriage market’ and the Victorian home could be a place of danger where all kinds of self-defence skills were needed. What I think all the writers examined in this book show is that there were some areas of life where the law couldn’t reach, and women had to be able to learn to protect themselves.

Q – Of all the heroines described in your book, who is your favorite, and why?

A – I admire the character of Judith Lee as she’s an independent spirit, and she can defend herself using jujitsu against a variety of criminals. I also think that the way an author writes about danger is as important as characterisation. While Judith Lee gets very angry, she has an understated, almost stiff-upper-lip way of talking about peril, which is quite amusing, a credit to the skills of her creator, Richard Marsh, was actually an intriguing figure himself.

Q – In what way?

A – He was involved in amateur dramatics before his writing career began, he also had a gift for portraying the mindsets and distinctive voices of his characters. He was author of the horror-thriller, The Beetle: A Mystery, which was published in 1897, the year in which Dracula appeared, and, according to a number of scholars, was more popular than Bram Stoker’s novel for some decades. Marsh also spent some time in jail, changed his name and became a prolific writer. What interests me about Marsh was that he combined horror and violence with humour in his stories. His work daringly referenced contemporary crimes such as the Whitechapel Murders – you can see shades of that in his Judith Lee story, Conscience. He really struck a chord with the public with his depiction of Judith Lee, who was in many ways Sherlock Holmes’s equivalent.

Q – You’re also the publicity officer for the H.G. Wells Society. How does Wells’ character Ann Veronica fit in with your theme?

A – I must say that don’t agree with all of Wells’s views on, for example, women, and some of his views are quite controversial today (he was in many ways a man of his time as well as being a forward thinker) but I think he’s a wonderful novelist and wordsmith whose work is both stirring, lightly humorous and cheekily iconoclastic. I do love his depiction of Ann Veronica, his Edwardian heroine, who wants to see life. A keen hockey player, she also learns jujitsu at high school and uses her knowledge of martial arts to defeat the rather sleazy Mr Ramage, who tries to take advantage of her in a locked hotel room. I think Wells sensitively portrays her feelings of guilt at having tackled him quite so effectively, but at least she does defend herself and doesn’t rely on a hero to come along and save her.

I see Judith Lee and Ann Veronica as early equivalents of feisty women in today’s literature and culture, particularly Buffy Summers from the Buffy the Vampire Slayer television series, Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games and even Anastasia Steele from Fifty Shades of Grey – they aren’t invulnerable, they suffer setbacks, deal with the ups and downs of love but they each have their own particular powers and channel their anger into the hand-to-hand defence of good causes.

Q – Finally, Emy, your book includes a chapter on Edith Garrud and the martial arts training of the Suffragettes. The image of the jujitsuffragettes is easily romanticised by modern readers. What would you say was the actual, and/or symbolic, social significance of Suffragettes training in the martial arts circa 1913?

A – I’m still making up my mind on that subject. On the one hand, I do agree that there is a tendency to romanticise jujitsuffragettes today, probably because the idea of a woman wearing a corset, big hair and an even bigger hat fighting a man and felling him to the floor cuts a bit of an incongruous yet charming and quaint image in the modern mind. I think some campaigners enjoyed the limelight too and, as H.G. Wells, suggests in Ann Veronica, some may have joined the movement to do something exciting. Some of them also espoused some more violent means which were controversial.

On the other hand, when you read what some militants went through in jail – sleep, hunger and thirst striking – and how they fought against the ignominy of force feeding (and the Bodyguard bravely protected their leaders from re-arrest and torture under the Cat and Mouse Act) you really get a sense of how brave these women were. I think that whether or not the vote was won by women’s war effort, the suffragettes, and indeed suffragists, raised the public consciousness with regard to female suffrage; it’s something I always think about when I put my cross on the ballot paper.

An interview with “Year of the Bodyguard” director Noel Burch

Our sincere thanks to Noel Burch, who agreed to answer some questions pertaining to his 1982 television docudrama The Year of the Bodyguard.

Q: Can you describe your interest in women’s self defence circa 1900?

A: I think I was first excited by the idea of women learning jiu-jitsu in the West at the beginning of the twentieth century when reading Kafka’s Amerika, in which Karl is humiliated by a young American woman with the then still mysterious art of jiu-jitsu

– and of course, since then I have understood that Kafka too was a masochist.

Many years later I came across a cover of Sandow’s Magazine where a “Mrs. Garrud throws her Japanese teacher”. I’m not sure how I found out about the Bodyguard, but it was still later, I think …

For years I had been a militant male feminist, and when I finally understood about the role of the Bodyguard in the suffragette movement, and had a privileged contact with Allan Fountain’s 11th Hour (documentary series) slot at Channel Four, I decided this was a good “politically correct” subject to propose, dealing as it did with women’s violence, and which would also fit in with my personal passion … which is actually alluded to in the film itself, on the demand of certain members of what was an almost exclusively female crew, including Debbie Kermode, daughter of Frank and a very hip feminist (she comes into the shot where I am challenged).

Q: How did you go about researching Year of the Bodyguard?

A: As I recall, I spent a good deal of time in a library in Hackney devoted to the suffragette movement. My main source was that book by Antonia Raeburn, which was, I believe, devoted to Edith Garrud and which several sequences in the film are copied from, including the pseudo-TV interview with “Edith Garrud” herself.

The hardest part was digging up and paying for the Blondie comic strip which opens the film and which had revealed my passion to myself at the age of 7.

Q: Can you describe the artistic/political choices you made in presenting the Bodyguard story for a television audience?

A: I wasn’t very interested in the TV audience, which may explain certain errors in the film, such as the Bernard Shaw Androcles excerpt, shot in an overly long shot to evoke the early cinema framing. The whole film was made as if I were working for the cinema.

The film reflects a long-term concern I had had with the hybrid documentary, involving different materials, different styles, etc. And involving here the mixing of periods – the TV interviews with Chesterton and with a bobby beaten by the women, etc. This was meant to be a pedagogical “de-alienating” form in those days, when we believed the classical film-language was “bourgeois”. I personally was into the forms of the early cinema as proto-avant-garde practice. I was writing a book about the emergence of film language. Today, I have problems with that avant-garde crap, but at the time, many of us working for Channel 4 were into that.

Q: I was wondering about the scene in which an actor playing a psychiatrist, in modern dress, is commenting on the psychological state of the suffragettes as masochists and martyrs. Was that monologue based on a published report, or was it written for the docudrama?

A: The psychiatrist scene, I wrote myself, possibly basing it on bits from the papers at the time, but more generally on a type of discourse we on the left all know from the dominant schools of analysis and therapy, tending to reduce political commitment to the individual psyche. Marcuse called it “neo-Freudian revisionism.”

Q: That seems apt. Changing tack, do you remember who served as your fight choreographer or martial arts advisor?

A: I had no martial arts advisor. I was the one who brought the actress some books and advice. I’ve been poring over (self defence) manuals for sixty years and I have a vast collection. She was the one who choreographed the demonstrations. She was both an aspiring actress and a teacher of women’s self-defence, and her physique vaguely resembled that of Edith Garrud; those were the reasons she was chosen.

Q: What was the public response to the docudrama?

A: I haven’t the slightest idea; does one ever know? The critics (but they are not the public!) were few and far between; not necessarily hostile, but nobody was very enthusiastic.

Q: How about individual reactions?

A: I remember one reaction by a former student of mine at the RCA, at the time a promising independent director but who now does routine work for the BBC. He felt that the scene where the bobby comes down to the gym where the women have just hidden their street-clothes under the tatami (mats) should have been filmed from the point of view of the police; it would have been more suspenseful, he thought. I tried to explain that I was on the side of the women, that the film was on the side of the women, that such a view-point would have been out of the question. He didn’t understand and, thirty year later, I think I understand why …

Q: I believe that the Suffragette Bodyguard was essentially fighting battles at two levels; the practicalities of street-fighting and evading the police, and as symbols of feminist militancy in the propaganda war against the Asquith government. Do you have any thoughts on that subject?

A: I really don’t know any more about the Bodyguard’s activities than you do, probably less, though your remark seems quite credible. But I should point out that when the film was shown to some committee at the BFI Production board at the time I was submitting a different project to this august body (which was turned down), some feminist historian, whose name I do not remember, was reported to have said “He doesn’t understand anything about the Bodyguard” or words to that effect. At the time I suspected this woman was simply picking up on the perverse underpinning of the film.

Q: Finally, are there any other anecdotes from the production that you’d like to share?

A: Well, after we had spent a whole day shooting that single long take where the women who have just smashed all the windows on Oxford Street take refuge in Mrs. Garrud’s studio (an authentic anecdote, drawn from Antonia Raeburn’s book), I was so happy to have achieved what was a kind of tour de force (a seven minute take, I think), that I failed to go thank that bunch of actresses who had been knocking themselves out all day for “my film” and they were complaining in the dressing room. My producer bawled me out and I tried to make amends.

Also, during the casting, there was one very beautiful actress who was quite skilled but whose agent wouldn’t let her be in the film because her role wasn’t important enough.

Also, and this is the best, the actor who plays the policeman on whom “Mrs. Garrud” does her demonstration at my reconstruction of the women’s festival, tried to get more money afterwards because he hadn’t been warned that he would be “hurt” (which he wasn’t at all, of course, it was just machismo … he didn’t like being thrown around by a woman!)