The new Netflix movie Enola Holmes stars Stranger Things actress Millie Bobby Brown in the title role as Sherlock Holmes’ younger sister. Based on the popular book series by Nancy Springer, the movie is the first mainstream production to feature suffrajitsu-style action as a major plot point (not counting the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it self-defence training scene in the 2015 movie Suffragette).

The new Netflix movie Enola Holmes stars Stranger Things actress Millie Bobby Brown in the title role as Sherlock Holmes’ younger sister. Based on the popular book series by Nancy Springer, the movie is the first mainstream production to feature suffrajitsu-style action as a major plot point (not counting the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it self-defence training scene in the 2015 movie Suffragette).

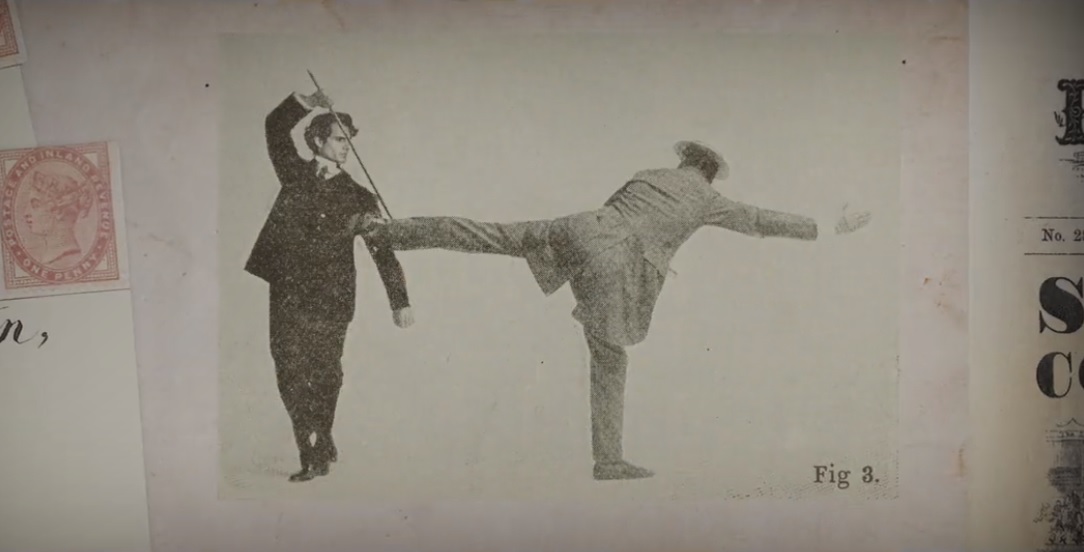

The first martial arts shout-out comes very early in the film. During a montage in which Enola admiringly describes her famous older brother’s many talents, viewers are treated to a cute animation based on Bartitsu founder E.W. Barton-Wright’s 1901 “Self Defence with a Walking Stick” article.

Bartitsu (or “baritsu”, as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle rendered it) was immortalised in Doyle’s 1903 short story The Adventure of the Empty House, in which Holmes explains that he’d used the art to defeat his arch-nemesis, Professor Moriarty, during their infamous battle at the brink of the Reichenbach Waterfall. The animation is especially notable in that Barton-Wright’s face has been replaced with that of Superman/The Witcher star Henry Cavill, who plays Sherlock Holmes.

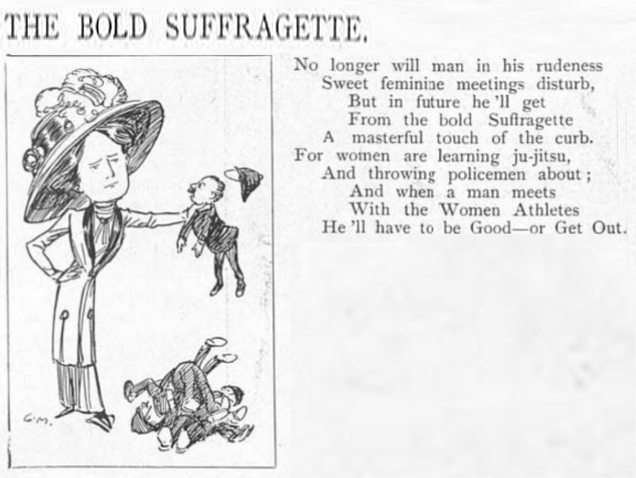

Having absconded from the Holmes family estate in search of their mysteriously missing radical suffragette mother Eudoria (played by Helena Bonham Carter), Enola makes her way to London where her investigations lead her to a women’s jiujitsu class taught by Edith Grayston (Susan Wokoma). Edith’s first name is clearly inspired by that of Edith Garrud, who was the first female professional jiujitsu instructor in the western world. It’s worth noting that Helena Bonham Carter’s character in Suffragette, self-defence instructor Edith Ellyn, was also named in honour of Mrs. Garrud, at the actresses’ own request. Enola Holmes is, thus, the second film in which Carter has been cast as a jiujitsu-fighting suffragette!

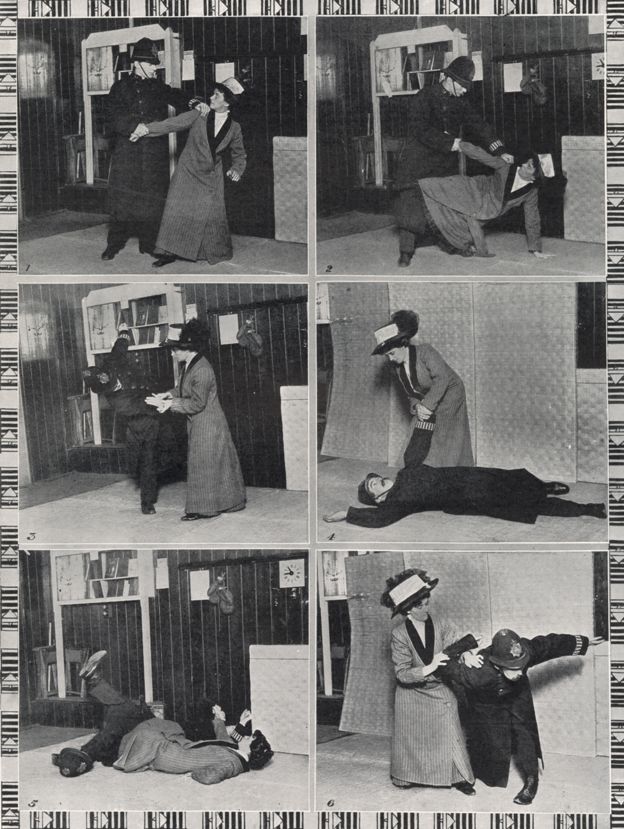

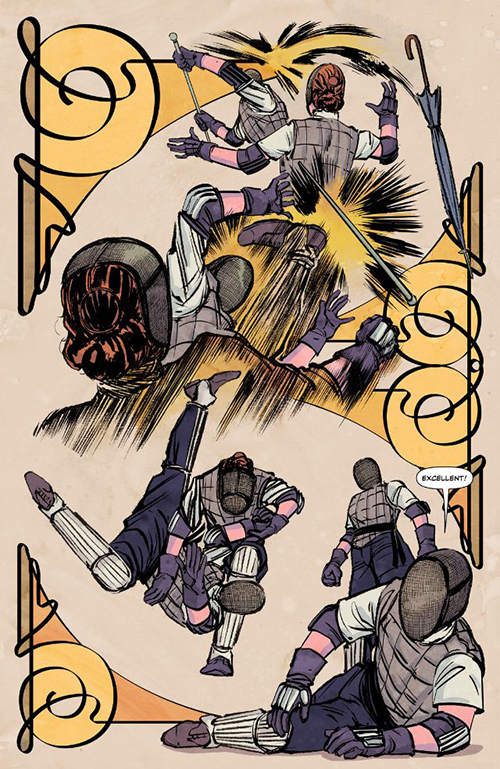

Allowing for the artistic license of portraying a women-only Japanese martial arts class in London during the year 1900 – the Bartitsu Club was open for business then and did offer women’s classes, but it would be another nine years before Edith Garrud started her “Suffragette Self Defence Club” – the class itself is highly accurate. The trainees’ uniforms are period-accurate hybrids of Japanese martial arts do-gi and Edwardian ladies’ physical culture kit and even the mats on the floor are typical of the quilted style used in circa 1900 gymnasia. The techniques being practiced by the jiujitsu trainees in the background of this scene are also entirely plausible for this time and place.

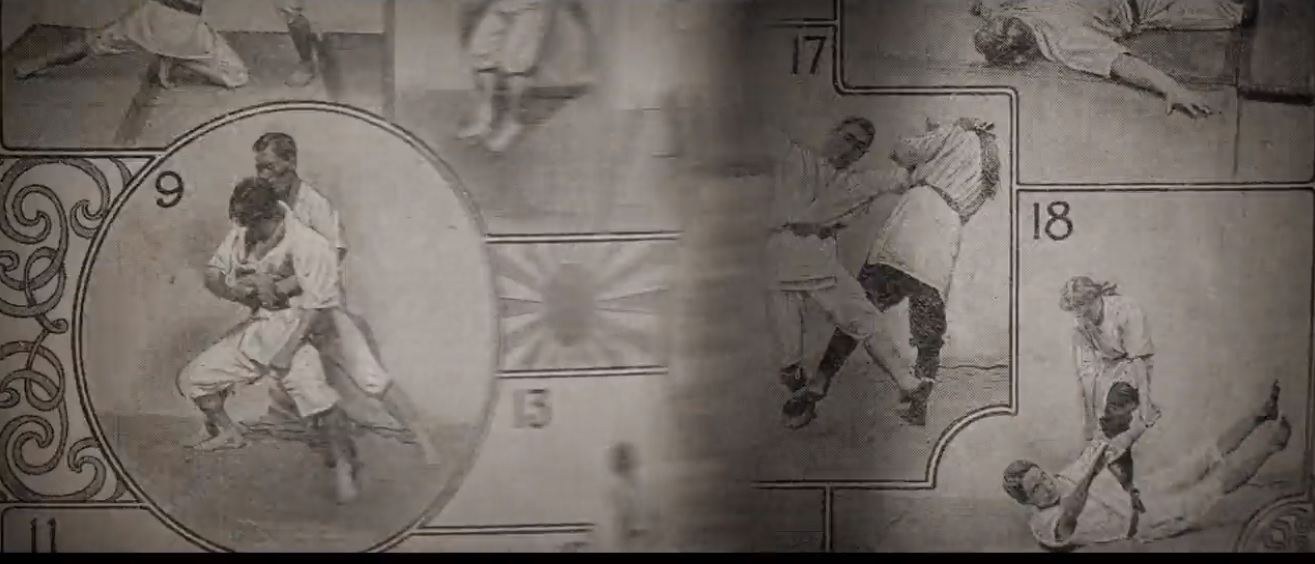

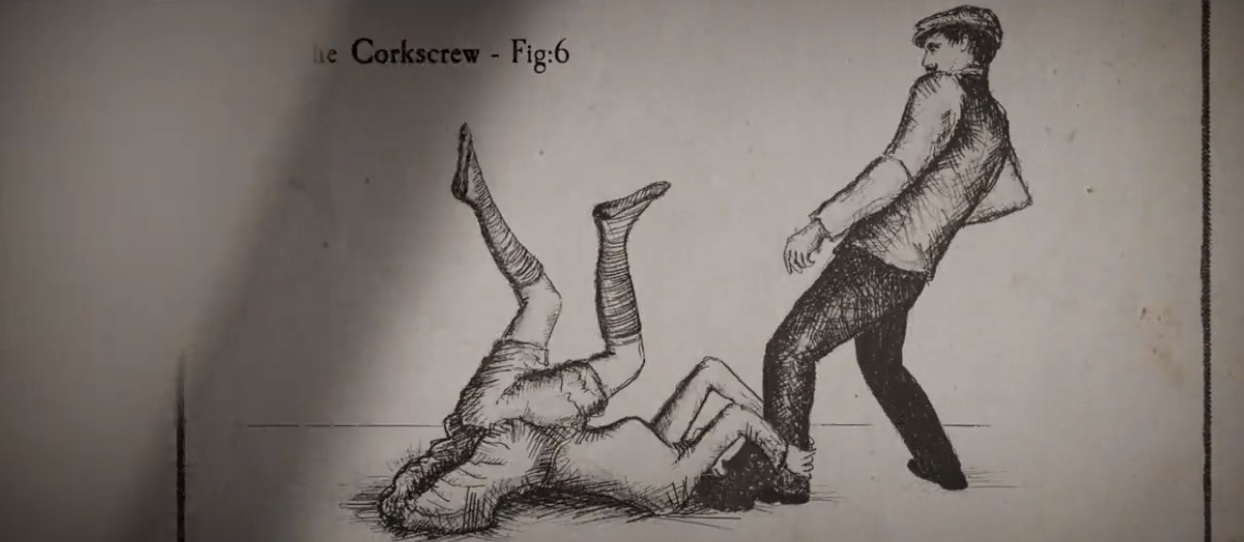

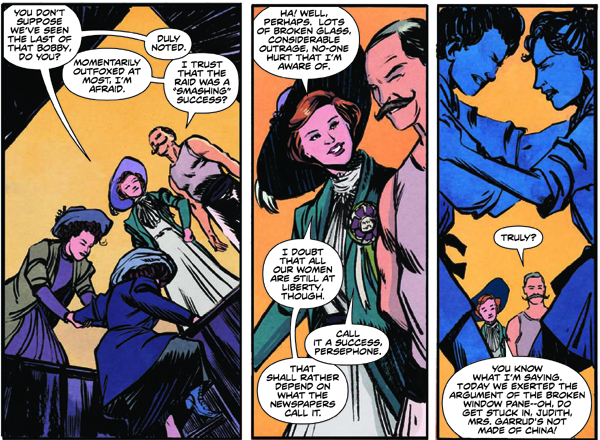

Retiring to the school’s office, Edith and Enola engage in a wary parlay – Edith clearly knows much more about Eudoria Holmes’ whereabouts that she’s prepared to reveal – and an impromptu, semi-playful physical challenge during which the frustrated Enola attempts a takedown nicknamed the “corkscrew”. This occasions another quick pictorial interlude, featuring a section of a (fictional) book titled Jujutsu: The Martial Art, whose cover may well have been inspired by the (real) Fine Art of Jujutsu, which was written by Emily Diana Watts in 1906.

We’re treated to a quick riff through the pages – which are montages of photographs from actual early 20th century jiujitsu magazine articles – and then a step-by-step guide to performing the corkscrew manoeuvre, which will clearly be significant later on in the story.

After some further skullduggery, Enola finds herself engaged in a desperate back-alley fight with walking-stick wielding assassin Linthorn (Burn Gorman) who is stalking her friend, the young Viscount Tewskbury, Marquess of Basilwether (Louis Partridge). This is, by far, the movie’s most elaborate and spectacular fight scene, well-choreographed by stunt co-ordinator Jo McLaren:

Although Enola again fails in attempting the corkscrew technique during this encounter, the astute viewer suspects that she’ll pull it off in the end … which is exactly what happens when, after many more machinations, she finds herself again at a disadvantage in taking on the same assassin, this time in the shadowy hallway of Viscount Tewksbury’s family manor:

Having rescued the hapless Tewksbury, it only remains for Enola to solve the Mystery of the Missing Mother – which does happen, after a fashion, though we suspect that there is more to discover in that regard during the inevitable and welcome sequel.

In the meantime, here’s a featurette on the fight scenes of Enola Holmes:

Suffragette is literally the first feature film to offer a dramatic representation of the radical women’s suffrage movement in England. As the movie has already been

Suffragette is literally the first feature film to offer a dramatic representation of the radical women’s suffrage movement in England. As the movie has already been  That noted, the film introduces protagonist Maud Watts (Carey Mulligan), a 24 year old East End laundress whose only joy in life is her family – husband Sonny (Ben Whishaw) and young son George (Adam Michael Dodd). Maud was born in the laundry; her mother died there when Maud was a young girl, the victim of an industrial accident, and Maud herself now bears the scars of a lifetime’s labor in that dangerous environment.

That noted, the film introduces protagonist Maud Watts (Carey Mulligan), a 24 year old East End laundress whose only joy in life is her family – husband Sonny (Ben Whishaw) and young son George (Adam Michael Dodd). Maud was born in the laundry; her mother died there when Maud was a young girl, the victim of an industrial accident, and Maud herself now bears the scars of a lifetime’s labor in that dangerous environment.

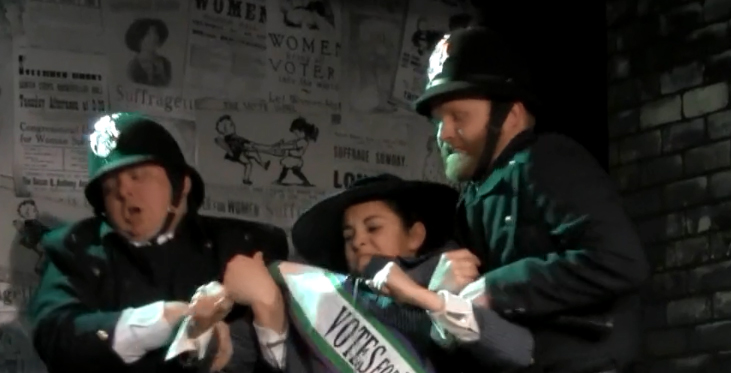

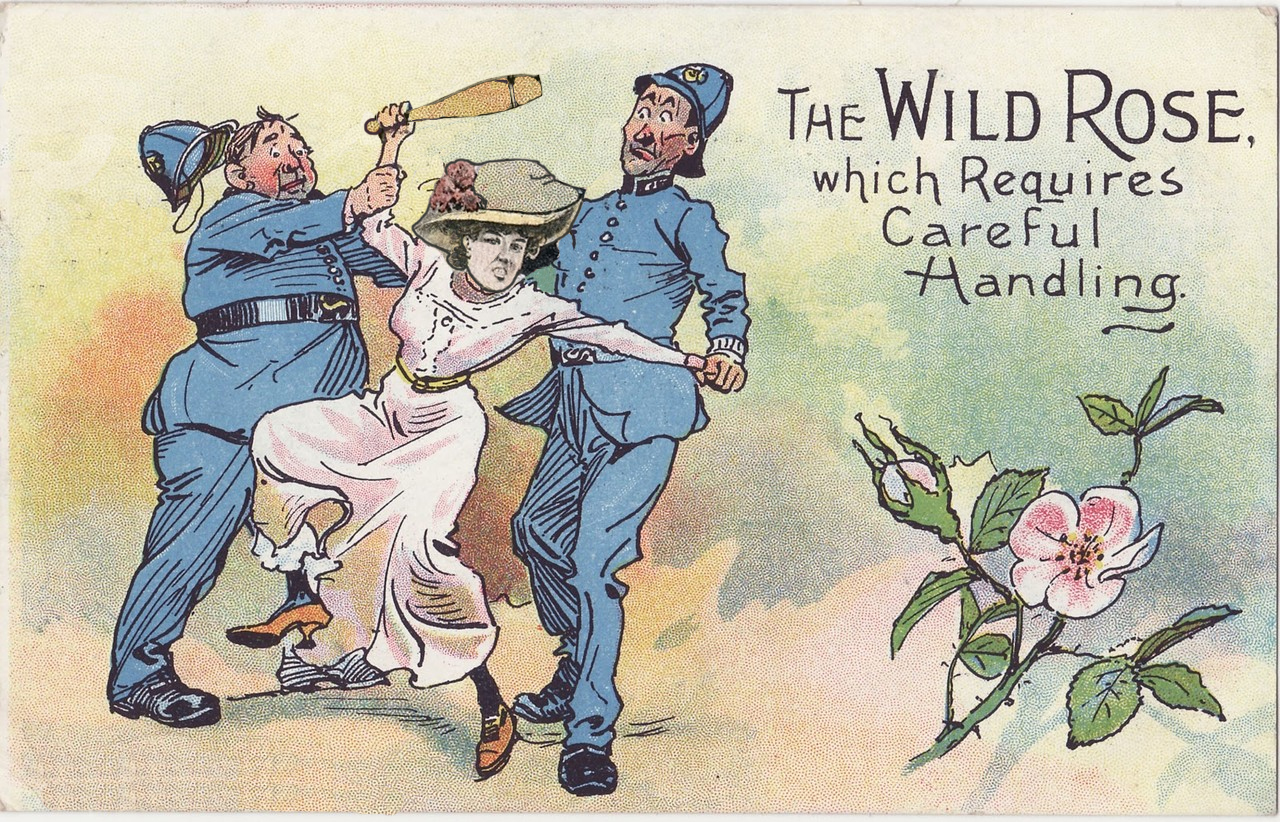

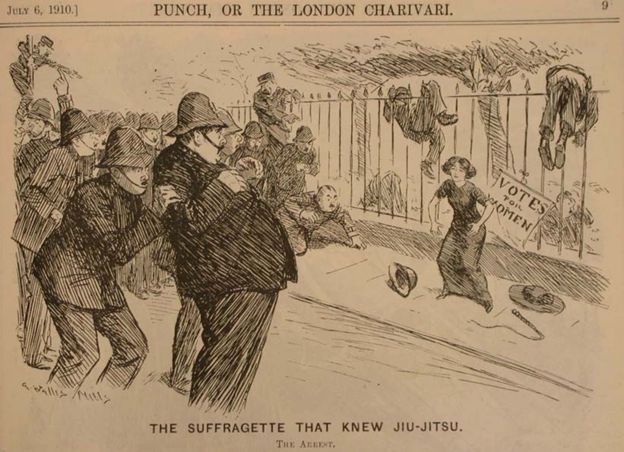

The police then violently disperse the suffragette crowd, striking women down with their truncheons and dragging them off to prison. The level of violence depicted is on the very extreme end of the scale of reported police action against suffragette protesters. The impression given is that the police assault was virtually unprovoked; this scene may have been inspired by the infamous

The police then violently disperse the suffragette crowd, striking women down with their truncheons and dragging them off to prison. The level of violence depicted is on the very extreme end of the scale of reported police action against suffragette protesters. The impression given is that the police assault was virtually unprovoked; this scene may have been inspired by the infamous

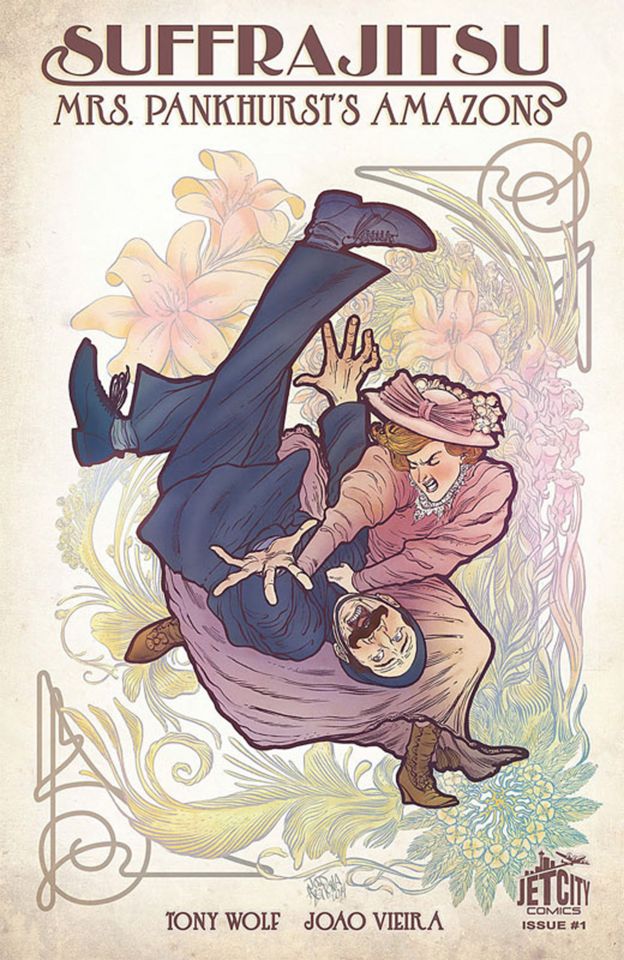

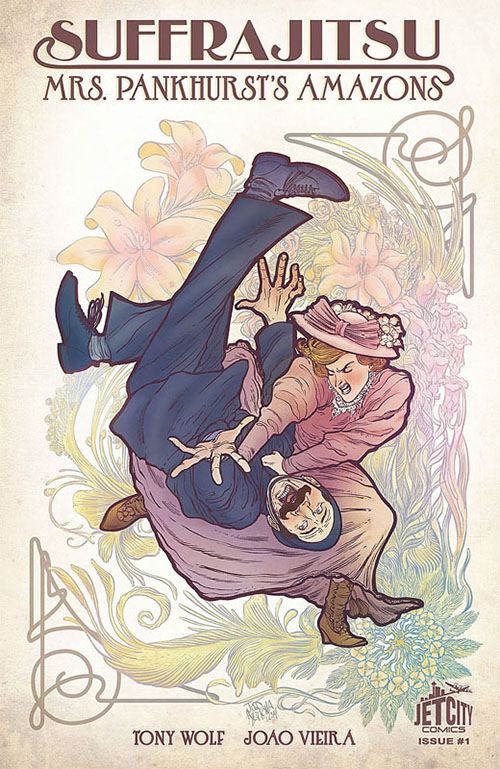

In sum, we unreservedly recommend the film to fans of the graphic novel. The cast is uniformly excellent and the evocation of London circa 1912/13 is beautifully executed. To some extent, in fact, the events of Suffragette can be viewed as an immediate prequel to those of the Suffrajitsu trilogy; it’s very easy to imagine Maud Watts as one of Mrs. Pankhurst’s Amazons.

In sum, we unreservedly recommend the film to fans of the graphic novel. The cast is uniformly excellent and the evocation of London circa 1912/13 is beautifully executed. To some extent, in fact, the events of Suffragette can be viewed as an immediate prequel to those of the Suffrajitsu trilogy; it’s very easy to imagine Maud Watts as one of Mrs. Pankhurst’s Amazons.